MASTER FRANCIS RABELAIS

FIVE BOOKS OF THE LIVES,

HEROIC DEEDS AND SAYINGS OF

GARGANTUA AND HIS SON PANTAGRUEL

BOOK I.

More: Book II,Book III,Book IV,Book V

Translated into English by

Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty

and

Peter Antony Motteux

The text of the first Two Books of Rabelais has been reprinted from the first edition (1653) of Urquhart's translation. Footnotes initialled 'M.' are drawn from the Maitland Club edition (1838); other footnotes are by the translator. Urquhart's translation of Book III. appeared posthumously in 1693, with a new edition of Books I. and II., under Motteux's editorship. Motteux's rendering of Books IV. and V. followed in 1708. Occasionally (as the footnotes indicate) passages omitted by Motteux have been restored from the 1738 copy edited by Ozell.

CONTENTS.

Chapter 1.I.—Of the Genealogy and Antiquity of Gargantua.

Chapter 1.III.—How Gargantua was carried eleven months in his mother's belly.

Chapter 1.IV.—-How Gargamelle, being great with Gargantua, did eat a huge deal of tripes.

Chapter 1.V.—The Discourse of the Drinkers.

Chapter 1.VI.—How Gargantua was born in a strange manner.

Chapter 1.VIII.—How they apparelled Gargantua.

Chapter 1.IX.—The colours and liveries of Gargantua.

Chapter 1.X.—Of that which is signified by the colours white and blue.

Chapter 1.XI.—Of the youthful age of Gargantua.

Chapter 1.XII.—Of Gargantua's wooden horses.

Chapter 1.XIV.—How Gargantua was taught Latin by a Sophister.

Chapter 1.XV.—How Gargantua was put under other schoolmasters.

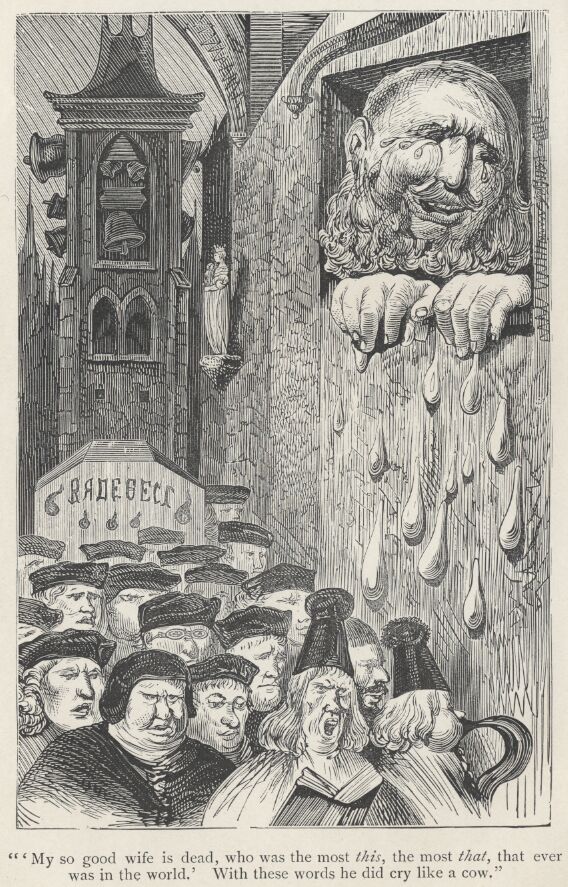

Chapter 1.XVIII.—How Janotus de Bragmardo was sent to Gargantua to recover the great bells.

Chapter 1.XIX.—The oration of Master Janotus de Bragmardo for recovery of the bells.

Chapter 1.XXII.—The games of Gargantua.

Chapter 1.XXIV.—How Gargantua spent his time in rainy weather.

Chapter 1.XXIX.—The tenour of the letter which Grangousier wrote to his son Gargantua.

Chapter 1.XXX.—How Ulric Gallet was sent unto Picrochole.

Chapter 1.XXXI.—The speech made by Gallet to Picrochole.

Chapter 1.XXXII.—How Grangousier, to buy peace, caused the cakes to be restored.

Chapter 1.XXXVIII.—How Gargantua did eat up six pilgrims in a salad.

Chapter 1.XLI.—How the Monk made Gargantua sleep, and of his hours and breviaries.

Chapter 1.XLII.—How the Monk encouraged his fellow-champions, and how he hanged upon a tree.

Chapter 1.XLVI.—How Grangousier did very kindly entertain Touchfaucet his prisoner.

Chapter 1.L.—Gargantua's speech to the vanquished.

Chapter 1.LI.—How the victorious Gargantuists were recompensed after the battle.

Chapter 1.LII.—How Gargantua caused to be built for the Monk the Abbey of Theleme.

Chapter 1.LIII.—How the abbey of the Thelemites was built and endowed.

Chapter 1.LIV.—The inscription set upon the great gate of Theleme.

Chapter 1.LV.—What manner of dwelling the Thelemites had.

Chapter 1.LVI.—How the men and women of the religious order of Theleme were apparelled.

Chapter 1.LVII.—How the Thelemites were governed, and of their manner of living.

Chapter 1.LVIII.—A prophetical Riddle.

List of Illustrations

Introduction.

Had Rabelais never written his strange and marvellous romance, no one would ever have imagined the possibility of its production. It stands outside other things—a mixture of mad mirth and gravity, of folly and reason, of childishness and grandeur, of the commonplace and the out-of-the-way, of popular verve and polished humanism, of mother-wit and learning, of baseness and nobility, of personalities and broad generalization, of the comic and the serious, of the impossible and the familiar. Throughout the whole there is such a force of life and thought, such a power of good sense, a kind of assurance so authoritative, that he takes rank with the greatest; and his peers are not many. You may like him or not, may attack him or sing his praises, but you cannot ignore him. He is of those that die hard. Be as fastidious as you will; make up your mind to recognize only those who are, without any manner of doubt, beyond and above all others; however few the names you keep, Rabelais' will always remain.

We may know his work, may know it well, and admire it more every time we read it. After being amused by it, after having enjoyed it, we may return again to study it and to enter more fully into its meaning. Yet there is no possibility of knowing his own life in the same fashion. In spite of all the efforts, often successful, that have been made to throw light on it, to bring forward a fresh document, or some obscure mention in a forgotten book, to add some little fact, to fix a date more precisely, it remains nevertheless full of uncertainty and of gaps. Besides, it has been burdened and sullied by all kinds of wearisome stories and foolish anecdotes, so that really there is more to weed out than to add.

This injustice, at first wilful, had its rise in the sixteenth century, in the furious attacks of a monk of Fontevrault, Gabriel de Puy-Herbault, who seems to have drawn his conclusions concerning the author from the book, and, more especially, in the regrettable satirical epitaph of Ronsard, piqued, it is said, that the Guises had given him only a little pavillon in the Forest of Meudon, whereas the presbytery was close to the chateau. From that time legend has fastened on Rabelais, has completely travestied him, till, bit by bit, it has made of him a buffoon, a veritable clown, a vagrant, a glutton, and a drunkard.

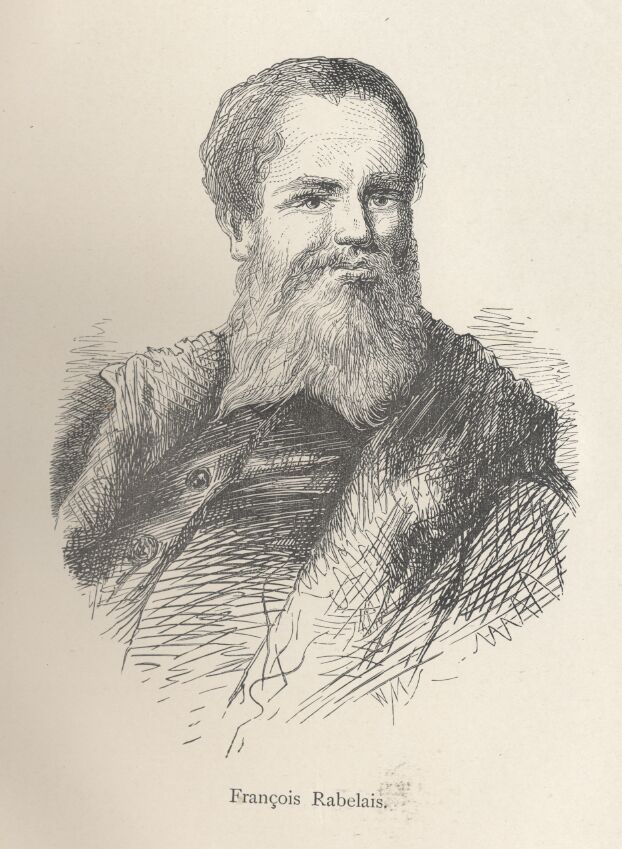

The likeness of his person has undergone a similar metamorphosis. He has been credited with a full moon of a face, the rubicund nose of an incorrigible toper, and thick coarse lips always apart because always laughing. The picture would have surprised his friends no less than himself. There have been portraits painted of Rabelais; I have seen many such. They are all of the seventeenth century, and the greater number are conceived in this jovial and popular style.

As a matter of fact there is only one portrait of him that counts, that has more than the merest chance of being authentic, the one in the Chronologie collee or coupee. Under this double name is known and cited a large sheet divided by lines and cross lines into little squares, containing about a hundred heads of illustrious Frenchmen. This sheet was stuck on pasteboard for hanging on the wall, and was cut in little pieces, so that the portraits might be sold separately. The majority of the portraits are of known persons and can therefore be verified. Now it can be seen that these have been selected with care, and taken from the most authentic sources; from statues, busts, medals, even stained glass, for the persons of most distinction, from earlier engravings for the others. Moreover, those of which no other copies exist, and which are therefore the most valuable, have each an individuality very distinct, in the features, the hair, the beard, as well as in the costume. Not one of them is like another. There has been no tampering with them, no forgery. On the contrary, there is in each a difference, a very marked personality. Leonard Gaultier, who published this engraving towards the end of the sixteenth century, reproduced a great many portraits besides from chalk drawings, in the style of his master, Thomas de Leu. It must have been such drawings that were the originals of those portraits which he alone has issued, and which may therefore be as authentic and reliable as the others whose correctness we are in a position to verify.

Now Rabelais has here nothing of the Roger Bontemps of low degree about him. His features are strong, vigorously cut, and furrowed with deep wrinkles; his beard is short and scanty; his cheeks are thin and already worn-looking. On his head he wears the square cap of the doctors and the clerks, and his dominant expression, somewhat rigid and severe, is that of a physician and a scholar. And this is the only portrait to which we need attach any importance.

This is not the place for a detailed biography, nor for an exhaustive study. At most this introduction will serve as a framework on which to fix a few certain dates, to hang some general observations. The date of Rabelais' birth is very doubtful. For long it was placed as far back as 1483: now scholars are disposed to put it forward to about 1495. The reason, a good one, is that all those whom he has mentioned as his friends, or in any real sense his contemporaries, were born at the very end of the fifteenth century. And, indeed, it is in the references in his romance to names, persons, and places, that the most certain and valuable evidence is to be found of his intercourse, his patrons, his friendships, his sojournings, and his travels: his own work is the best and richest mine in which to search for the details of his life.

Like Descartes and Balzac, he was a native of Touraine, and Tours and Chinon have only done their duty in each of them erecting in recent years a statue to his honour, a twofold homage reflecting credit both on the province and on the town. But the precise facts about his birth are nevertheless vague. Huet speaks of the village of Benais, near Bourgeuil, of whose vineyards Rabelais makes mention. As the little vineyard of La Deviniere, near Chinon, and familiar to all his readers, is supposed to have belonged to his father, Thomas Rabelais, some would have him born there. It is better to hold to the earlier general opinion that Chinon was his native town; Chinon, whose praises he sang with such heartiness and affection. There he might well have been born in the Lamproie house, which belonged to his father, who, to judge from this circumstance, must have been in easy circumstances, with the position of a well-to-do citizen. As La Lamproie in the seventeenth century was a hostelry, the father of Rabelais has been set down as an innkeeper. More probably he was an apothecary, which would fit in with the medical profession adopted by his son in after years. Rabelais had brothers, all older than himself. Perhaps because he was the youngest, his father destined him for the Church.

The time he spent while a child with the Benedictine monks at Seuille is uncertain. There he might have made the acquaintance of the prototype of his Friar John, a brother of the name of Buinart, afterwards Prior of Sermaize. He was longer at the Abbey of the Cordeliers at La Baumette, half a mile from Angers, where he became a novice. As the brothers Du Bellay, who were later his Maecenases, were then studying at the University of Angers, where it is certain he was not a student, it is doubtless from this youthful period that his acquaintance and alliance with them should date. Voluntarily, or induced by his family, Rabelais now embraced the ecclesiastical profession, and entered the monastery of the Franciscan Cordeliers at Fontenay-le-Comte, in Lower Poitou, which was honoured by his long sojourn at the vital period of his life when his powers were ripening. There it was he began to study and to think, and there also began his troubles.

In spite of the wide-spread ignorance among the monks of that age, the encyclopaedic movement of the Renaissance was attracting all the lofty minds. Rabelais threw himself into it with enthusiasm, and Latin antiquity was not enough for him. Greek, a study discountenanced by the Church, which looked on it as dangerous and tending to freethought and heresy, took possession of him. To it he owed the warm friendship of Pierre Amy and of the celebrated Guillaume Bude. In fact, the Greek letters of the latter are the best source of information concerning this period of Rabelais' life. It was at Fontenay-le-Comte also that he became acquainted with the Brissons and the great jurist Andre Tiraqueau, whom he never mentions but with admiration and deep affection. Tiraqueau's treatise, De legibus connubialibus, published for the first time in 1513, has an important bearing on the life of Rabelais. There we learn that, dissatisfied with the incomplete translation of Herodotus by Laurent Valla, Rabelais had retranslated into Latin the first book of the History. That translation unfortunately is lost, as so many other of his scattered works. It is probably in this direction that the hazard of fortune has most discoveries and surprises in store for the lucky searcher. Moreover, as in this law treatise Tiraqueau attacked women in a merciless fashion, President Amaury Bouchard published in 1522 a book in their defence, and Rabelais, who was a friend of both the antagonists, took the side of Tiraqueau. It should be observed also in passing, that there are several pages of such audacious plain-speaking, that Rabelais, though he did not copy these in his Marriage of Panurge, has there been, in his own fashion, as out spoken as Tiraqueau. If such freedom of language could be permitted in a grave treatise of law, similar liberties were certainly, in the same century, more natural in a book which was meant to amuse.

The great reproach always brought against Rabelais is not the want of reserve of his language merely, but his occasional studied coarseness, which is enough to spoil his whole work, and which lowers its value. La Bruyere, in the chapter Des ouvrages de l'esprit, not in the first edition of the Caracteres, but in the fifth, that is to say in 1690, at the end of the great century, gives us on this subject his own opinion and that of his age:

'Marot and Rabelais are inexcusable in their habit of scattering filth about their writings. Both of them had genius enough and wit enough to do without any such expedient, even for the amusement of those persons who look more to the laugh to be got out of a book than to what is admirable in it. Rabelais especially is incomprehensible. His book is an enigma,—one may say inexplicable. It is a Chimera; it is like the face of a lovely woman with the feet and the tail of a reptile, or of some creature still more loathsome. It is a monstrous confusion of fine and rare morality with filthy corruption. Where it is bad, it goes beyond the worst; it is the delight of the basest of men. Where it is good, it reaches the exquisite, the very best; it ministers to the most delicate tastes.'

Putting aside the rather slight connection established between two men of whom one is of very little importance compared with the other, this is otherwise very admirably said, and the judgment is a very just one, except with regard to one point—the misunderstanding of the atmosphere in which the book was created, and the ignoring of the examples of a similar tendency furnished by literature as well as by the popular taste. Was it not the Ancients that began it? Aristophanes, Catullus, Petronius, Martial, flew in the face of decency in their ideas as well as in the words they used, and they dragged after them in this direction not a few of the Latin poets of the Renaissance, who believed themselves bound to imitate them. Is Italy without fault in this respect? Her story-tellers in prose lie open to easy accusation. Her Capitoli in verse go to incredible lengths; and the astonishing success of Aretino must not be forgotten, nor the licence of the whole Italian comic theatre of the sixteenth century. The Calandra of Bibbiena, who was afterwards a Cardinal, and the Mandragola of Machiavelli, are evidence enough, and these were played before Popes, who were not a whit embarrassed. Even in England the drama went very far for a time, and the comic authors of the reign of Charles II., evidently from a reaction, and to shake off the excess and the wearisomeness of Puritan prudery and affectation, which sent them to the opposite extreme, are not exactly noted for their reserve. But we need not go beyond France. Slight indications, very easily verified, are all that may be set down here; a formal and detailed proof would be altogether too dangerous.

Thus, for instance, the old Fabliaux—the Farces of the fifteenth century, the story-tellers of the sixteenth—reveal one of the sides, one of the veins, so to speak, of our literature. The art that addresses itself to the eye had likewise its share of this coarseness. Think of the sculptures on the capitals and the modillions of churches, and the crude frankness of certain painted windows of the fifteenth century. Queen Anne was, without any doubt, one of the most virtuous women in the world. Yet she used to go up the staircase of her chateau at Blois, and her eyes were not offended at seeing at the foot of a bracket a not very decent carving of a monk and a nun. Neither did she tear out of her book of Hours the large miniature of the winter month, in which, careless of her neighbours' eyes, the mistress of the house, sitting before her great fireplace, warms herself in a fashion which it is not advisable that dames of our age should imitate. The statue of Cybele by the Tribolo, executed for Francis I., and placed, not against a wall, but in the middle of Queen Claude's chamber at Fontainebleau, has behind it an attribute which would have been more in place on a statue of Priapus, and which was the symbol of generativeness. The tone of the conversations was ordinarily of a surprising coarseness, and the Precieuses, in spite of their absurdities, did a very good work in setting themselves in opposition to it. The worthy Chevalier de La-Tour-Landry, in his Instructions to his own daughters, without a thought of harm, gives examples which are singular indeed, and in Caxton's translation these are not omitted. The Adevineaux Amoureux, printed at Bruges by Colard Mansion, are astonishing indeed when one considers that they were the little society diversions of the Duchesses of Burgundy and of the great ladies of a court more luxurious and more refined than the French court, which revelled in the Cent Nouvelles of good King Louis XI. Rabelais' pleasantry about the woman folle a la messe is exactly in the style of the Adevineaux.

A later work than any of his, the Novelle of Bandello, should be kept in mind—for the writer was Bishop of Agen, and his work was translated into French—as also the Dames Galantes of Brantome. Read the Journal of Heroard, that honest doctor, who day by day wrote down the details concerning the health of Louis XIII. from his birth, and you will understand the tone of the conversation of Henry IV. The jokes at a country wedding are trifles compared with this royal coarseness. Le Moyen de Parvenir is nothing but a tissue and a mass of filth, and the too celebrated Cabinet Satyrique proves what, under Louis XIII., could be written, printed, and read. The collection of songs formed by Clairambault shows that the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were no purer than the sixteenth. Some of the most ribald songs are actually the work of Princesses of the royal House.

It is, therefore, altogether unjust to make Rabelais the scapegoat, to charge him alone with the sins of everybody else. He spoke as those of his time used to speak; when amusing them he used their language to make himself understood, and to slip in his asides, which without this sauce would never have been accepted, would have found neither eyes nor ears. Let us blame not him, therefore, but the manners of his time.

Besides, his gaiety, however coarse it may appear to us—and how rare a thing is gaiety!—has, after all, nothing unwholesome about it; and this is too often overlooked. Where does he tempt one to stray from duty? Where, even indirectly, does he give pernicious advice? Whom has he led to evil ways? Does he ever inspire feelings that breed misconduct and vice, or is he ever the apologist of these? Many poets and romance writers, under cover of a fastidious style, without one coarse expression, have been really and actively hurtful; and of that it is impossible to accuse Rabelais. Women in particular quickly revolt from him, and turn away repulsed at once by the archaic form of the language and by the outspokenness of the words. But if he be read aloud to them, omitting the rougher parts and modernizing the pronunciation, it will be seen that they too are impressed by his lively wit as by the loftiness of his thought. It would be possible, too, to extract, for young persons, without modification, admirable passages of incomparable force. But those who have brought out expurgated editions of him, or who have thought to improve him by trying to rewrite him in modern French, have been fools for their pains, and their insulting attempts have had, and always will have, the success they deserve.

His dedications prove to what extent his whole work was accepted. Not to speak of his epistolary relations with Bude, with the Cardinal d'Armagnac and with Pellissier, the ambassador of Francis I. and Bishop of Maguelonne, or of his dedication to Tiraqueau of his Lyons edition of the Epistolae Medicinales of Giovanni Manardi of Ferrara, of the one addressed to the President Amaury Bouchard of the two legal texts which he believed antique, there is still the evidence of his other and more important dedications. In 1532 he dedicated his Hippocrates and his Galen to Geoffroy d'Estissac, Bishop of Maillezais, to whom in 1535 and 1536 he addressed from Rome the three news letters, which alone have been preserved; and in 1534 he dedicated from Lyons his edition of the Latin book of Marliani on the topography of Rome to Jean du Bellay (at that time Bishop of Paris) who was raised to the Cardinalate in 1535. Beside these dedications we must set the privilege of Francis I. of September, 1545, and the new privilege granted by Henry II. on August 6th, 1550, Cardinal de Chatillon present, for the third book, which was dedicated, in an eight-lined stanza, to the Spirit of the Queen of Navarre. These privileges, from the praises and eulogies they express in terms very personal and very exceptional, are as important in Rabelais' life as were, in connection with other matters, the Apostolic Pastorals in his favour. Of course, in these the popes had not to introduce his books of diversions, which, nevertheless, would have seemed in their eyes but very venial sins. The Sciomachie of 1549, an account of the festivities arranged at Rome by Cardinal du Bellay in honour of the birth of the second son of Henry II., was addressed to Cardinal de Guise, and in 1552 the fourth book was dedicated, in a new prologue, to Cardinal de Chatillon, the brother of Admiral de Coligny.

These are no unknown or insignificant personages, but the greatest lords and princes of the Church. They loved and admired and protected Rabelais, and put no restrictions in his way. Why should we be more fastidious and severe than they were? Their high contemporary appreciation gives much food for thought.

There are few translations of Rabelais in foreign tongues; and certainly the task is no light one, and demands more than a familiarity with ordinary French. It would have been easier in Italy than anywhere else. Italian, from its flexibility and its analogy to French, would have lent itself admirably to the purpose; the instrument was ready, but the hand was not forthcoming. Neither is there any Spanish translation, a fact which can be more easily understood. The Inquisition would have been a far more serious opponent than the Paris' Sorbonne, and no one ventured on the experiment. Yet Rabelais forces comparison with Cervantes, whose precursor he was in reality, though the two books and the two minds are very different. They have only one point in common, their attack and ridicule of the romances of chivalry and of the wildly improbable adventures of knight-errants. But in Don Quixote there is not a single detail which would suggest that Cervantes knew Rabelais' book or owed anything to it whatsoever, even the starting-point of his subject. Perhaps it was better he should not have been influenced by him, in however slight a degree; his originality is the more intact and the more genial.

On the other hand, Rabelais has been several times translated into German. In the present century Regis published at Leipsic, from 1831 to 1841, with copious notes, a close and faithful translation. The first one cannot be so described, that of Johann Fischart, a native of Mainz or Strasburg, who died in 1614. He was a Protestant controversialist, and a satirist of fantastic and abundant imagination. In 1575 appeared his translation of Rabelais' first book, and in 1590 he published the comic catalogue of the library of Saint Victor, borrowed from the second book. It is not a translation, but a recast in the boldest style, full of alterations and of exaggerations, both as regards the coarse expressions which he took upon himself to develop and to add to, and in the attacks on the Roman Catholic Church. According to Jean Paul Richter, Fischart is much superior to Rabelais in style and in the fruitfulness of his ideas, and his equal in erudition and in the invention of new expressions after the manner of Aristophanes. He is sure that his work was successful, because it was often reprinted during his lifetime; but this enthusiasm of Jean Paul would hardly carry conviction in France. Who treads in another's footprints must follow in the rear. Instead of a creator, he is but an imitator. Those who take the ideas of others to modify them, and make of them creations of their own, like Shakespeare in England, Moliere and La Fontaine in France, may be superior to those who have served them with suggestions; but then the new works must be altogether different, must exist by themselves. Shakespeare and the others, when they imitated, may be said always to have destroyed their models. These copyists, if we call them so, created such works of genius that the only pity is they are so rare. This is not the case with Fischart, but it would be none the less curious were some one thoroughly familiar with German to translate Fischart for us, or at least, by long extracts from him, give an idea of the vagaries of German taste when it thought it could do better than Rabelais. It is dangerous to tamper with so great a work, and he who does so runs a great risk of burning his fingers.

England has been less daring, and her modesty and discretion have brought her success. But, before speaking of Urquhart's translation, it is but right to mention the English-French Dictionary of Randle Cotgrave, the first edition of which dates from 1611. It is in every way exceedingly valuable, and superior to that of Nicot, because instead of keeping to the plane of classic and Latin French, it showed an acquaintance with and mastery of the popular tongue as well as of the written and learned language. As a foreigner, Cotgrave is a little behind in his information. He is not aware of all the changes and novelties of the passing fashion. The Pleiad School he evidently knew nothing of, but kept to the writers of the fifteenth and the first half of the sixteenth century. Thus words out of Rabelais, which he always translates with admirable skill, are frequent, and he attaches to them their author's name. So Rabelais had already crossed the Channel, and was read in his own tongue. Somewhat later, during the full sway of the Commonwealth—and Maitre Alcofribas Nasier must have been a surprising apparition in the midst of Puritan severity—Captain Urquhart undertook to translate him and to naturalize him completely in England.

Thomas Urquhart belonged to a very old family of good standing in the North of Scotland. After studying in Aberdeen he travelled in France, Spain, and Italy, where his sword was as active as that intelligent curiosity of his which is evidenced by his familiarity with three languages and the large library which he brought back, according to his own account, from sixteen countries he had visited.

On his return to England he entered the service of Charles I., who knighted him in 1641. Next year, after the death of his father, he went to Scotland to set his family affairs in order, and to redeem his house in Cromarty. But, in spite of another sojourn in foreign lands, his efforts to free himself from pecuniary embarrassments were unavailing. At the king's death his Scottish loyalty caused him to side with those who opposed the Parliament. Formally proscribed in 1649, taken prisoner at the defeat of Worcester in 1651, stripped of all his belongings, he was brought to London, but was released on parole at Cromwell's recommendation. After receiving permission to spend five months in Scotland to try once more to settle his affairs, he came back to London to escape from his creditors. And there he must have died, though the date of his death is unknown. It probably took place after 1653, the date of the publication of the two first books, and after having written the translation of the third, which was not printed from his manuscript till the end of the seventeenth century.

His life was therefore not without its troubles, and literary activity must have been almost his only consolation. His writings reveal him as the strangest character, fantastic, and full of a naive vanity, which, even at the time he was translating the genealogy of Gargantua—surely well calculated to cure any pondering on his own—caused him to trace his unbroken descent from Adam, and to state that his family name was derived from his ancestor Esormon, Prince of Achaia, 2139 B.C., who was surnamed Ourochartos, that is to say the Fortunate and the Well-beloved. A Gascon could not have surpassed this.

Gifted as he was, learned in many directions, an enthusiastic mathematician, master of several languages, occasionally full of wit and humour, and even good sense, yet he gave his books the strangest titles, and his ideas were no less whimsical. His style is mystic, fastidious, and too often of a wearisome length and obscurity; his verses rhyme anyhow, or not at all; but vivacity, force and heat are never lacking, and the Maitland Club did well in reprinting, in 1834, his various works, which are very rare. Yet, in spite of their curious interest, he owes his real distinction and the survival of his name to his translation of Rabelais.

The first two books appeared in 1653. The original edition, exceedingly scarce, was carefully reprinted in 1838, only a hundred copies being issued, by an English bibliophile T(heodore) M(artin), whose interesting preface I regret to sum up so cursorily. At the end of the seventeenth century, in 1693, a French refugee, Peter Antony Motteux, whose English verses and whose plays are not without value, published in a little octavo volume a reprint, very incorrect as to the text, of the first two books, to which he added the third, from the manuscript found amongst Urquhart's papers. The success which attended this venture suggested to Motteux the idea of completing the work, and a second edition, in two volumes, appeared in 1708, with the translation of the fourth and fifth books, and notes. Nineteen years after his death, John Ozell, translator on a large scale of French, Italian, and Spanish authors, revised Motteux's edition, which he published in five volumes in 1737, adding Le Duchat's notes; and this version has often been reprinted since.

The continuation by Motteux, who was also the translator of Don Quixote, has merits of its own. It is precise, elegant, and very faithful. Urquhart's, without taking liberties with Rabelais like Fischart, is not always so closely literal and exact. Nevertheless, it is much superior to Motteux's. If Urquhart does not constantly adhere to the form of the expression, if he makes a few slight additions, not only has he an understanding of the original, but he feels it, and renders the sense with a force and a vivacity full of warmth and brilliancy. His own learning made the comprehension of the work easy to him, and his anglicization of words fabricated by Rabelais is particularly successful. The necessity of keeping to his text prevented his indulgence in the convolutions and divagations dictated by his exuberant fancy when writing on his own account. His style, always full of life and vigour, is here balanced, lucid, and picturesque. Never elsewhere did he write so well. And thus the translation reproduces the very accent of the original, besides possessing a very remarkable character of its own. Such a literary tone and such literary qualities are rarely found in a translation. Urquhart's, very useful for the interpretation of obscure passages, may, and indeed should be read as a whole, both for Rabelais and for its own merits.

Holland, too, possesses a translation of Rabelais. They knew French in that country in the seventeenth century better than they do to-day, and there Rabelais' works were reprinted when no editions were appearing in France. This Dutch translation was published at Amsterdam in 1682, by J. Tenhoorn. The name attached to it, Claudio Gallitalo (Claudius French-Italian) must certainly be a pseudonym. Only a Dutch scholar could identify the translator, and state the value to be assigned to his work.

Rabelais' style has many different sources. Besides its force and brilliancy, its gaiety, wit, and dignity, its abundant richness is no less remarkable. It would be impossible and useless to compile a glossary of Voltaire's words. No French writer has used so few, and all of them are of the simplest. There is not one of them that is not part of the common speech, or which demands a note or an explanation. Rabelais' vocabulary, on the other hand, is of an astonishing variety. Where does it all come from? As a fact, he had at his command something like three languages, which he used in turn, or which he mixed according to the effect he wished to produce.

First of all, of course, he had ready to his hand the whole speech of his time, which had no secrets for him. Provincials have been too eager to appropriate him, to make of him a local author, the pride of some village, in order that their district might have the merit of being one of the causes, one of the factors of his genius. Every neighbourhood where he ever lived has declared that his distinction was due to his knowledge of its popular speech. But these dialect-patriots have fallen out among themselves. To which dialect was he indebted? Was it that of Touraine, or Berri, or Poitou, or Paris? It is too often forgotten, in regard to French patois—leaving out of count the languages of the South—that the words or expressions that are no longer in use to-day are but a survival, a still living trace of the tongue and the pronunciation of other days. Rabelais, more than any other writer, took advantage of the happy chances and the richness of the popular speech, but he wrote in French, and nothing but French. That is why he remains so forcible, so lucid, and so living, more living even—speaking only of his style out of charity to the others—than any of his contemporaries.

It has been said that great French prose is solely the work of the seventeenth century. There were nevertheless, before that, two men, certainly very different and even hostile, who were its initiators and its masters, Calvin on the one hand, on the other Rabelais.

Rabelais had a wonderful knowledge of the prose and the verse of the fifteenth century: he was familiar with Villon, Pathelin, the Quinze Joies de Mariage, the Cent Nouvelles, the chronicles and the romances, and even earlier works, too, such as the Roman de la Rose. Their words, their turns of expression came naturally to his pen, and added a piquancy and, as it were, a kind of gloss of antique novelty to his work. He fabricated words, too, on Greek and Latin models, with great ease, sometimes audaciously and with needless frequency. These were for him so many means, so many elements of variety. Sometimes he did this in mockery, as in the humorous discourse of the Limousin scholar, for which he is not a little indebted to Geoffroy Tory in the Champfleury; sometimes, on the contrary, seriously, from a habit acquired in dealing with classical tongues.

Again, another reason of the richness of his vocabulary was that he invented and forged words for himself. Following the example of Aristophanes, he coined an enormous number of interminable words, droll expressions, sudden and surprising constructions. What had made Greece and the Athenians laugh was worth transporting to Paris.

With an instrument so rich, resources so endless, and the skill to use them, it is no wonder that he could give voice to anything, be as humorous as he could be serious, as comic as he could be grave, that he could express himself and everybody else, from the lowest to the highest. He had every colour on his palette, and such skill was in his fingers that he could depict every variety of light and shade.

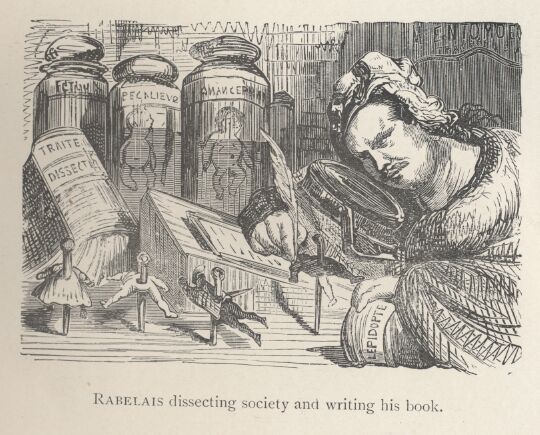

We have evidence that Rabelais did not always write in the same fashion. The Chronique Gargantuaine is uniform in style and quite simple, but cannot with certainty be attributed to him. His letters are bombastic and thin; his few attempts at verse are heavy, lumbering, and obscure, altogether lacking in harmony, and quite as bad as those of his friend, Jean Bouchet. He had no gift of poetic form, as indeed is evident even from his prose. And his letters from Rome to the Bishop of Maillezais, interesting as they are in regard to the matter, are as dull, bare, flat, and dry in style as possible. Without his signature no one would possibly have thought of attributing them to him. He is only a literary artist when he wishes to be such; and in his romance he changes the style completely every other moment: it has no constant character or uniform manner, and therefore unity is almost entirely wanting in his work, while his endeavours after contrast are unceasing. There is throughout the whole the evidence of careful and conscious elaboration.

Hence, however lucid and free be the style of his romance, and though its flexibility and ease seem at first sight to have cost no trouble at all, yet its merit lies precisely in the fact that it succeeds in concealing the toil, in hiding the seams. He could not have reached this perfection at a first attempt. He must have worked long at the task, revised it again and again, corrected much, and added rather than cut away. The aptness of form and expression has been arrived at by deliberate means, and owes nothing to chance. Apart from the toning down of certain bold passages, to soften their effect, and appease the storm—for these were not literary alterations, but were imposed on him by prudence—one can see how numerous are the variations in his text, how necessary it is to take account of them, and to collect them. A good edition, of course, would make no attempt at amalgamating these. That would give a false impression and end in confusion; but it should note them all, and show them all, not combined, but simply as variations.

After Le Duchat, all the editions, in their care that nothing should be lost, made the mistake of collecting and placing side by side things which had no connection with each other, which had even been substituted for each other. The result was a fabricated text, full of contradictions naturally. But since the edition issued by M. Jannet, the well-known publisher of the Bibliotheque Elzevirienne, who was the first to get rid of this patchwork, this mosaic, Rabelais' latest text has been given, accompanied by all the earlier variations, to show the changes he made, as well as his suppressions and additions. It would also be possible to reverse the method. It would be interesting to take his first text as the basis, noting the later modifications. This would be quite as instructive and really worth doing. Perhaps one might then see more clearly with what care he made his revisions, after what fashion he corrected, and especially what were the additions he made.

No more striking instance can be quoted than the admirable chapter about the shipwreck. It was not always so long as Rabelais made it in the end: it was much shorter at first. As a rule, when an author recasts some passage that he wishes to revise, he does so by rewriting the whole, or at least by interpolating passages at one stroke, so to speak. Nothing of the kind is seen here. Rabelais suppressed nothing, modified nothing; he did not change his plan at all. What he did was to make insertions, to slip in between two clauses a new one. He expressed his meaning in a lengthier way, and the former clause is found in its integrity along with the additional one, of which it forms, as it were, the warp. It was by this method of touching up the smallest details, by making here and there such little noticeable additions, that he succeeded in heightening the effect without either change or loss. In the end it looks as if he had altered nothing, added nothing new, as if it had always been so from the first, and had never been meddled with.

The comparison is most instructive, showing us to what an extent Rabelais' admirable style was due to conscious effort, care, and elaboration, a fact which is generally too much overlooked, and how instead of leaving any trace which would reveal toil and study, it has on the contrary a marvellous cohesion, precision, and brilliancy. It was modelled and remodelled, repaired, touched up, and yet it has all the appearance of having been created at a single stroke, or of having been run like molten wax into its final form.

Something should be said here of the sources from which Rabelais borrowed. He was not the first in France to satirize the romances of chivalry. The romance in verse by Baudouin de Sebourc, printed in recent years, was a parody of the Chansons de Geste. In the Moniage Guillaume, and especially in the Moniage Rainouart, in which there is a kind of giant, and occasionally a comic giant, there are situations and scenes which remind us of Rabelais. The kind of Fabliaux in mono-rhyme quatrains of the old Aubery anticipate his coarse and popular jests. But all that is beside the question; Rabelais did not know these. Nothing is of direct interest save what was known to him, what fell under his eyes, what lay to his hand—as the Facetiae of Poggio, and the last sermonnaires. In the course of one's reading one may often enough come across the origin of some of Rabelais' witticisms; here and there we may discover how he has developed a situation. While gathering his materials wherever he could find them, he was nevertheless profoundly original.

On this point much research and investigation might be employed. But there is no need why these researches should be extended to the region of fancy. Gargantua has been proved by some to be of Celtic origin. Very often he is a solar myth, and the statement that Rabelais only collected popular traditions and gave new life to ancient legends is said to be proved by the large number of megalithic monuments to which is attached the name of Gargantua. It was, of course, quite right to make a list of these, to draw up, as it were, a chart of them, but the conclusion is not justified. The name, instead of being earlier, is really later, and is a witness, not to the origin, but to the success and rapid popularity of his novel. No one has ever yet produced a written passage or any ancient testimony to prove the existence of the name before Rabelais. To place such a tradition on a sure basis, positive traces must be forthcoming; and they cannot be adduced even for the most celebrated of these monuments, since he mentions himself the great menhir near Poitiers, which he christened by the name of Passelourdin. That there is something in the theory is possible. Perrault found the subjects of his stories in the tales told by mothers and nurses. He fixed them finally by writing them down. Floating about vaguely as they were, he seized them, worked them up, gave them shape, and yet of scarcely any of them is there to be found before his time a single trace. So we must resign ourselves to know just as little of what Gargantua and Pantagruel were before the sixteenth century.

In a book of a contemporary of Rabelais, the Legende de Pierre Faifeu by the Angevin, Charles de Bourdigne, the first edition of which dates from 1526 and the second 1531—both so rare and so forgotten that the work is only known since the eighteenth century by the reprint of Custelier—in the introductory ballad which recommends this book to readers, occur these lines in the list of popular books which Faifeu would desire to replace:

'Laissez ester Caillette le folastre, Les quatre filz Aymon vestuz de bleu, Gargantua qui a cheveux de plastre.'

He has not 'cheveux de plastre' in Rabelais. If the rhyme had not suggested the phrase—and the exigencies of the strict form of the ballade and its forced repetitions often imposed an idea which had its whole origin in the rhyme—we might here see a dramatic trace found nowhere else. The name of Pantagruel is mentioned too, incidentally, in a Mystery of the fifteenth century. These are the only references to the names which up till now have been discovered, and they are, as one sees, of but little account.

On the other hand, the influence of Aristophanes and of Lucian, his intimate acquaintance with nearly all the writers of antiquity, Greek as well as Latin, with whom Rabelais is more permeated even than Montaigne, were a mine of inspiration. The proof of it is everywhere. Pliny especially was his encyclopaedia, his constant companion. All he says of the Pantagruelian herb, though he amply developed it for himself, is taken from Pliny's chapter on flax. And there is a great deal more of this kind to be discovered, for Rabelais does not always give it as quotation. On the other hand, when he writes, 'Such an one says,' it would be difficult enough to find who is meant, for the 'such an one' is a fictitious writer. The method is amusing, but it is curious to account of it.

The question of the Chronique Gargantuaine is still undecided. Is it by Rabelais or by someone else? Both theories are defensible, and can be supported by good reasons. In the Chronique everything is heavy, occasionally meaningless, and nearly always insipid. Can the same man have written the Chronique and Gargantua, replaced a book really commonplace by a masterpiece, changed the facts and incidents, transformed a heavy icy pleasantry into a work glowing with wit and life, made it no longer a mass of laborious trifling and cold-blooded exaggerations but a satire on human life of the highest genius? Still there are points common to the two. Besides, Rabelais wrote other things; and it is only in his romance that he shows literary skill. The conception of it would have entered his mind first only in a bare and summary fashion. It would have been taken up again, expanded, developed, metamorphosed. That is possible, and, for my part, I am of those who, like Brunet and Nodier, are inclined to think that the Chronique, in spite of its inferiority, is really a first attempt, condemned as soon as the idea was conceived in another form. As its earlier date is incontestable, we must conclude that if the Chronique is not by him, his Gargantua and its continuation would not have existed without it. This would be a great obligation to stand under to some unknown author, and in that case it is astonishing that his enemies did not reproach him during his lifetime with being merely an imitator and a plagiarist. So there are reasons for and against his authorship of it, and it would be dangerous to make too bold an assertion.

One fact which is absolutely certain and beyond all controversy, is that Rabelais owed much to one of his contemporaries, an Italian, to the Histoire Macaronique of Merlin Coccaie. Its author, Theophilus Folengo, who was also a monk, was born in 1491, and died only a short time before Rabelais, in 1544. But his burlesque poem was published in 1517. It was in Latin verse, written in an elaborately fabricated style. It is not dog Latin, but Latin ingeniously italianized, or rather Italian, even Mantuan, latinized. The contrast between the modern form of the word and its Roman garb produces the most amusing effect. In the original it is sometimes difficult to read, for Folengo has no objection to using the most colloquial words and phrases.

The subject is quite different. It is the adventures of Baldo, son of Guy de Montauban, the very lively history of his youth, his trial, imprisonment and deliverance, his journey in search of his father, during which he visits the Planets and Hell. The narration is constantly interrupted by incidental adventures. Occasionally they are what would be called to-day very naturalistic, and sometimes they are madly extravagant.

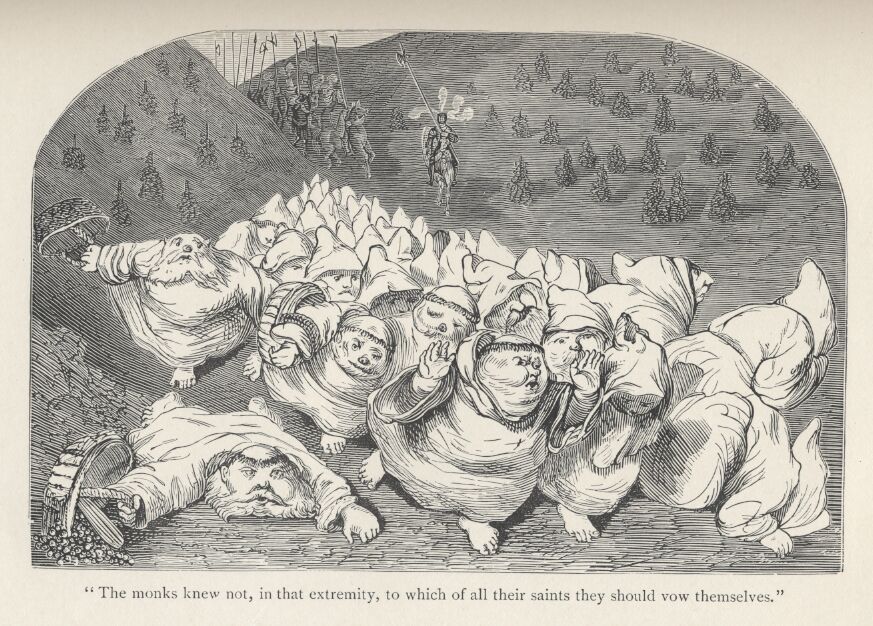

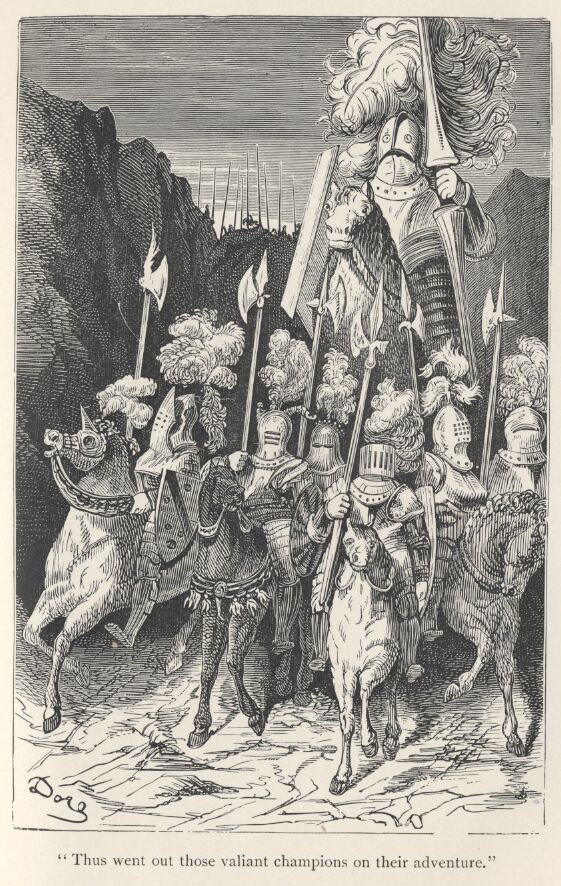

But Fracasso, Baldo's friend, is a giant; another friend, Cingar, who delivers him, is Panurge exactly, and quite as much given to practical joking. The women in the senile amour of the old Tognazzo, the judges, and the poor sergeants, are no more gently dealt with by Folengo than by the monk of the Iles d'Hyeres. If Dindenaut's name does not occur, there are the sheep. The tempest is there, and the invocation to all the saints. Rabelais improves all he borrows, but it is from Folengo he starts. He does not reproduce the words, but, like the Italian, he revels in drinking scenes, junkettings, gormandizing, battles, scuffles, wounds and corpses, magic, witches, speeches, repeated enumerations, lengthiness, and a solemnly minute precision of impossible dates and numbers. The atmosphere, the tone, the methods are the same, and to know Rabelais well, you must know Folengo well too.

Detailed proof of this would be too lengthy a matter; one would have to quote too many passages, but on this question of sources nothing is more interesting than a perusal of the Opus Macaronicorum. It was translated into French only in 1606—Paris, Gilley Robinot. This translation of course cannot reproduce all the many amusing forms of words, but it is useful, nevertheless, in showing more clearly the points of resemblance between the two works,—how far in form, ideas, details, and phrases Rabelais was permeated by Folengo. The anonymous translator saw this quite well, and said so in his title, 'Histoire macaronique de Merlin Coccaie, prototype of Rabelais.' It is nothing but the truth, and Rabelais, who does not hide it from himself, on more than one occasion mentions the name of Merlin Coccaie.

Besides, Rabelais was fed on the Italians of his time as on the Greeks and Romans. Panurge, who owes much to Cingar, is also not free from obligations to the miscreant Margutte in the Morgante Maggiore of Pulci. Had Rabelais in his mind the tale from the Florentine Chronicles, how in the Savonarola riots, when the Piagnoni and the Arrabiati came to blows in the church of the Dominican convent of San-Marco, Fra Pietro in the scuffle broke the heads of the assailants with the bronze crucifix he had taken from the altar? A well-handled cross could so readily be used as a weapon, that probably it has served as such more than once, and other and even quite modern instances might be quoted.

But other Italian sources are absolutely certain. There are few more wonderful chapters in Rabelais than the one about the drinkers. It is not a dialogue: those short exclamations exploding from every side, all referring to the same thing, never repeating themselves, and yet always varying the same theme. At the end of the Novelle of Gentile Sermini of Siena, there is a chapter called Il Giuoco della pugna, the Game of Battle. Here are the first lines of it: 'Apre, apre, apre. Chi gioca, chi gioca —uh, uh!—A Porrione, a Porrione.—Viela, viela; date a ognuno.—Alle mantella, alle mantella.—Oltre di corsa; non vi fermate.—Voltate qui; ecco costoro; fate veli innanzi.—Viela, viela; date costi.—Chi la fa? Io—Ed io.—Dagli; ah, ah, buona fu.—Or cosi; alla mascella, al fianco. —Dagli basso; di punta, di punta.—Ah, ah, buon gioco, buon gioco.'

And thus it goes on with fire and animation for pages. Rabelais probably translated or directly imitated it. He changed the scene; there was no giuooco della pugna in France. He transferred to a drinking-bout this clatter of exclamations which go off by themselves, which cross each other and get no answer. He made a wonderful thing of it. But though he did not copy Sermini, yet Sermini's work provided him with the form of the subject, and was the theme for Rabelais' marvellous variations.

Who does not remember the fantastic quarrel of the cook with the poor devil who had flavoured his dry bread with the smoke of the roast, and the judgment of Seyny John, truly worthy of Solomon? It comes from the Cento Novelle Antiche, rewritten from tales older than Boccaccio, and moreover of an extreme brevity and dryness. They are only the framework, the notes, the skeleton of tales. The subject is often wonderful, but nothing is made of it: it is left unshaped. Rabelais wrote a version of one, the ninth. The scene takes place, not at Paris, but at Alexandria in Egypt among the Saracens, and the cook is called Fabrac. But the surprise at the end, the sagacious judgment by which the sound of a piece of money was made the price of the smoke, is the same. Now the first dated edition of the Cento Novelle (which were frequently reprinted) appeared at Bologna in 1525, and it is certain that Rabelais had read the tales. And there would be much else of the same kind to learn if we knew Rabelais' library.

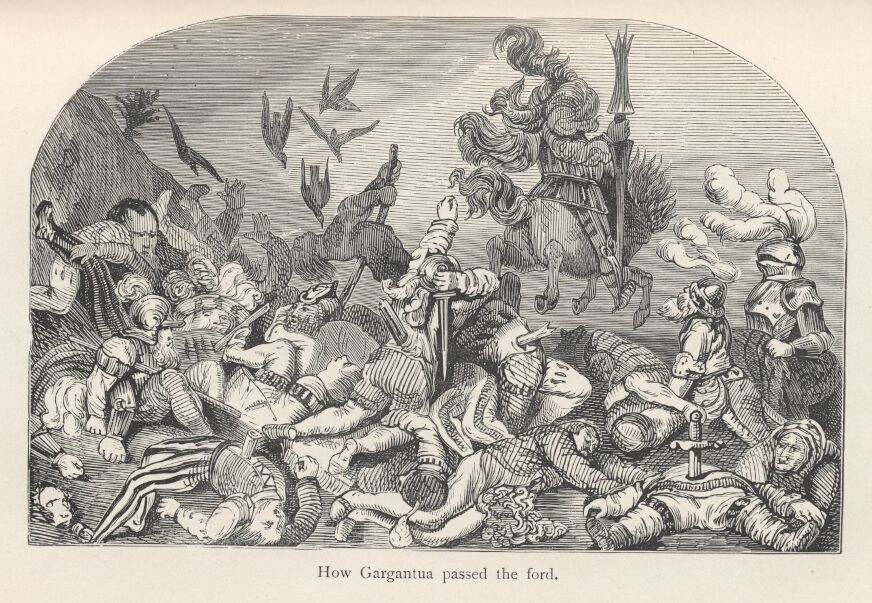

A still stranger fact of this sort may be given to show how nothing came amiss to him. He must have known, and even copied the Latin Chronicle of the Counts of Anjou. It is accepted, and rightly so, as an historical document, but that is no reason for thinking that the truth may not have been manipulated and adorned. The Counts of Anjou were not saints. They were proud, quarrelsome, violent, rapacious, and extravagant, as greedy as they were charitable to the Church, treacherous and cruel. Yet their anonymous panegyrist has made them patterns of all the virtues. In reality it is both a history and in some sort a romance; especially is it a collection of examples worthy of being followed, in the style of the Cyropaedia, our Juvenal of the fifteenth century, and a little like Fenelon's Telemaque. Now in it there occurs the address of one of the counts to those who rebelled against him and who were at his mercy. Rabelais must have known it, for he has copied it, or rather, literally translated whole lines of it in the wonderful speech of Gargantua to the vanquished. His contemporaries, who approved of his borrowing from antiquity, could not detect this one, because the book was not printed till much later. But Rabelais lived in Maine. In Anjou, which often figures among the localities he names, he must have met with and read the Chronicles of the Counts in manuscript, probably in some monastery library, whether at Fontenay-le-Comte or elsewhere it matters little. There is not only a likeness in the ideas and tone, but in the words too, which cannot be a mere matter of chance. He must have known the Chronicles of the Counts of Anjou, and they inspired one of his finest pages. One sees, therefore, how varied were the sources whence he drew, and how many of them must probably always escape us.

When, as has been done for Moliere, a critical bibliography of the works relating to Rabelais is drawn up—which, by the bye, will entail a very great amount of labour—the easiest part will certainly be the bibliography of the old editions. That is the section that has been most satisfactorily and most completely worked out. M. Brunet said the last word on the subject in his Researches in 1852, and in the important article in the fifth edition of his Manuel du Libraire (iv., 1863, pp. 1037-1071).

The facts about the fifth book cannot be summed up briefly. It was printed as a whole at first, without the name of the place, in 1564, and next year at Lyons by Jean Martin. It has given, and even still gives rise to two contradictory opinions. Is it Rabelais' or not?

First of all, if he had left it complete, would sixteen years have gone by before it was printed? Then, does it bear evident marks of his workmanship? Is the hand of the master visible throughout? Antoine Du Verdier in the 1605 edition of his Prosopographie writes: '(Rabelais') misfortune has been that everybody has wished to "pantagruelize!" and several books have appeared under his name, and have been added to his works, which are not by him, as, for instance, l'Ile Sonnante, written by a certain scholar of Valence and others.'

The scholar of Valence might be Guillaume des Autels, to whom with more certainty can be ascribed the authorship of a dull imitation of Rabelais, the History of Fanfreluche and Gaudichon, published in 1578, which, to say the least of it, is very much inferior to the fifth book.

Louis Guyon, in his Diverses Lecons, is still more positive: 'As to the last book which has been included in his works, entitled l'Ile Sonnante, the object of which seems to be to find fault with and laugh at the members and the authorities of the Catholic Church, I protest that he did not compose it, for it was written long after his death. I was at Paris when it was written, and I know quite well who was its author; he was not a doctor.' That is very emphatic, and it is impossible to ignore it.

Yet everyone must recognize that there is a great deal of Rabelais in the fifth book. He must have planned it and begun it. Remembering that in 1548 he had published, not as an experiment, but rather as a bait and as an announcement, the first eleven chapters of the fourth book, we may conclude that the first sixteen chapters of the fifth book published by themselves nine years after his death, in 1562, represent the remainder of his definitely finished work. This is the more certain because these first chapters, which contain the Apologue of the Horse and the Ass and the terrible Furred Law-cats, are markedly better than what follows them. They are not the only ones where the master's hand may be traced, but they are the only ones where no other hand could possibly have interfered.

In the remainder the sentiment is distinctly Protestant. Rabelais was much struck by the vices of the clergy and did not spare them. Whether we are unable to forgive his criticisms because they were conceived in a spirit of raillery, or whether, on the other hand, we feel admiration for him on this point, yet Rabelais was not in the least a sectary. If he strongly desired a moral reform, indirectly pointing out the need of it in his mocking fashion, he was not favourable to a political reform. Those who would make of him a Protestant altogether forget that the Protestants of his time were not for him, but against him. Henri Estienne, for instance, Ramus, Theodore de Beze, and especially Calvin, should know how he was to be regarded. Rabelais belonged to what may be called the early reformation, to that band of honest men in the beginning of the sixteenth century, precursors of the later one perhaps, but, like Erasmus, between the two extremes. He was neither Lutheran nor Calvinist, neither German nor Genevese, and it is quite natural that his work was not reprinted in Switzerland, which would certainly have happened had the Protestants looked on him as one of themselves.

That Rabelais collected the materials for the fifth book, had begun it, and got on some way, there can be no doubt: the excellence of a large number of passages prove it, but—taken as a whole—the fifth book has not the value, the verve, and the variety of the others. The style is quite different, less rich, briefer, less elaborate, drier, in parts even wearisome. In the first four books Rabelais seldom repeats himself. The fifth book contains from the point of view of the vocabulary really the least novelty. On the contrary, it is full of words and expressions already met with, which is very natural in an imitation, in a copy, forced to keep to a similar tone, and to show by such reminders and likenesses that it is really by the same pen. A very striking point is the profound difference in the use of anatomical terms. In the other books they are most frequently used in a humorous sense, and nonsensically, with a quite other meaning than their own; in the fifth they are applied correctly. It was necessary to include such terms to keep up the practice, but the writer has not thought of using them to add to the comic effect: one cannot always think of everything. Trouble has been taken, of course, to include enumerations, but there are much fewer fabricated and fantastic words. In short, the hand of the maker is far from showing the same suppleness and strength.

A eulogistic quatrain is signed Nature quite, which, it is generally agreed, is an anagram of Jean Turquet. Did the adapter of the fifth book sign his work in this indirect fashion? He might be of the Genevese family to whom Louis Turquet and his son Theodore belonged, both well-known, and both strong Protestants. The obscurity relating to this matter is far from being cleared up, and perhaps never will be.

It fell to my lot—here, unfortunately, I am forced to speak of a personal matter—to print for the first time the manuscript of the fifth book. At first it was hoped it might be in Rabelais' own hand; afterwards that it might be at least a copy of his unfinished work. The task was a difficult one, for the writing, extremely flowing and rapid, is execrable, and most difficult to decipher and to transcribe accurately. Besides, it often happens in the sixteenth and the end of the fifteenth century, that manuscripts are much less correct than the printed versions, even when they have not been copied by clumsy and ignorant hands. In this case, it is the writing of a clerk executed as quickly as possible. The farther it goes the more incorrect it becomes, as if the writer were in haste to finish.

What is really the origin of it? It has less the appearance of notes or fragments prepared by Rabelais than of a first attempt at revision. It is not an author's rough draft; still less is it his manuscript. If I had not printed this enigmatical text with scrupulous and painful fidelity, I would do it now. It was necessary to do it so as to clear the way. But as the thing is done, and accessible to those who may be interested, and who wish to critically examine it, there is no further need of reprinting it. All the editions of Rabelais continue, and rightly, to reproduce the edition of 1564. It is not the real Rabelais, but however open to criticism it may be, it was under that form that the fifth book appeared in the sixteenth century, under that form it was accepted. Consequently it is convenient and even necessary to follow and keep to the original edition.

The first sixteen chapters may, and really must be, the text of Rabelais, in the final form as left by him, and found after his death; the framework, and a number of the passages in the continuation, the best ones, of course, are his, but have been patched up and tampered with. Nothing can have been suppressed of what existed; it was evidently thought that everything should be admitted with the final revision; but the tone was changed, additions were made, and 'improvements.' Adapters are always strangely vain.

In the seventeenth century, the French printing-press, save for an edition issued at Troyes in 1613, gave up publishing Rabelais, and the work passed to foreign countries. Jean Fuet reprinted him at Antwerp in 1602. After the Amsterdam edition of 1659, where for the first time appears 'The Alphabet of the French Author,' comes the Elzevire edition of 1663. The type, an imitation of what made the reputation of the little volumes of the Gryphes of Lyons, is charming, the printing is perfect, and the paper, which is French—the development of paper-making in Holland and England did not take place till after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes—is excellent. They are pretty volumes to the eye, but, as in all the reprints of the seventeenth century, the text is full of faults and most untrustworthy.

France, through a representative in a foreign land, however, comes into line again in the beginning of the eighteenth century, and in a really serious fashion, thanks to the very considerable learning of a French refugee, Jacob Le Duchat, who died in 1748. He had a most thorough knowledge of the French prose-writers of the sixteenth century, and he made them accessible by his editions of the Quinze Joies du Mariage, of Henri Estienne, of Agrippa d'Aubigne, of L'Etoile, and of the Satyre Menippee. In 1711 he published an edition of Rabelais at Amsterdam, through Henry Bordesius, in five duodecimo volumes. The reprint in quarto which he issued in 1741, seven years before his death, is, with its engravings by Bernard Picot, a fine library edition. Le Duchat's is the first of the critical editions. It takes account of differences in the texts, and begins to point out the variations. His very numerous notes are remarkable, and are still worthy of most serious consideration. He was the first to offer useful elucidations, and these have been repeated after him, and with good reason will continue to be so. The Abbe de Massy's edition of 1752, also an Amsterdam production, has made use of Le Duchat's but does not take its place. Finally, at the end of the century, Cazin printed Rabelais in his little volume, in 1782, and Bartiers issued two editions (of no importance) at Paris in 1782 and 1798. Fortunately the nineteenth century has occupied itself with the great 'Satyrique' in a more competent and useful fashion.

In 1820 L'Aulnaye published through Desoer his three little volumes, printed in exquisite style, and which have other merits besides. His volume of annotations, in which, that nothing might be lost of his own notes, he has included many things not directly relating to Rabelais, is full of observations and curious remarks which are very useful additions to Le Duchat. One fault to be found with him is his further complication of the spelling. This he did in accordance with a principle that the words should be referred to their real etymology. Learned though he was, Rabelais had little care to be so etymological, and it is not his theories but those of the modern scholar that have been ventilated.

Somewhat later, from 1823 to 1826, Esmangart and Johanneau issued a variorum edition in nine volumes, in which the text is often encumbered by notes which are really too numerous, and, above all, too long. The work was an enormous one, but the best part of it is Le Duchat's, and what is not his is too often absolutely hypothetical and beside the truth. Le Duchat had already given too much importance to the false historical explanation. Here it is constantly coming in, and it rests on no evidence. In reality, there is no need of the key to Rabelais by which to discover the meaning of subtle allusions. He is neither so complicated nor so full of riddles. We know how he has scattered the names of contemporaries about his work, sometimes of friends, sometimes of enemies, and without disguising them under any mask. He is no more Panurge than Louis XII. is Gargantua or Francis I. Pantagruel. Rabelais says what he wants, all he wants, and in the way he wants. There are no mysteries below the surface, and it is a waste of time to look for knots in a bulrush. All the historical explanations are purely imaginary, utterly without proof, and should the more emphatically be looked on as baseless and dismissed. They are radically false, and therefore both worthless and harmful.

In 1840 there appeared in the Bibliotheque Charpentier the Rabelais in a single duodecimo volume, begun by Charles Labiche, and, after his death, completed by M. Paul Lacroix, whose share is the larger. The text is that of L'Aulnaye; the short footnotes, with all their brevity, contain useful explanations of difficult words. Amongst the editions of Rabelais this is one of the most important, because it brought him many readers and admirers. No other has made him so well and so widely known as this portable volume, which has been constantly reprinted. No other has been so widely circulated, and the sale still goes on. It was, and must still be looked on as a most serviceable edition.

The edition published by Didot in 1857 has an altogether special character. In the biographical notice M. Rathery for the first time treated as they deserve the foolish prejudices which have made Rabelais misunderstood, and M. Burgaud des Marets set the text on a quite new base. Having proved, what of course is very evident, that in the original editions the spelling, and the language too, were of the simplest and clearest, and were not bristling with the nonsensical and superfluous consonants which have given rise to the idea that Rabelais is difficult to read, he took the trouble first of all to note the spelling of each word. Whenever in a single instance he found it in accordance with modern spelling, he made it the same throughout. The task was a hard one, and Rabelais certainly gained in clearness, but over-zeal is often fatal to a reform. In respect to its precision and the value of its notes, which are short and very judicious, Burgaud des Marets' edition is valuable, and is amongst those which should be known and taken into account.

Since Le Duchat all the editions have a common fault. They are not exactly guilty of fabricating, but they set up an artificial text in the sense that, in order to lose as little as possible, they have collected and united what originally were variations—the revisions, in short, of the original editions. Guided by the wise counsels given by Brunet in 1852 in his Researches on the old editions of Rabelais, Pierre Jannet published the first three books in 1858; then, when the publication of the Bibliotheque Elzevirienne was discontinued, he took up the work again and finished the edition in Picard's blue library, in little volumes, each book quite distinct. It was M. Jannet who in our days first restored the pure and exact text of Rabelais, not only without retouching it, but without making additions or insertions, or juxtaposition of things that were not formerly found together. For each of the books he has followed the last edition issued by Rabelais, and all the earlier differences he gives as variations. It is astonishing that a thing so simple and so fitting should not have been done before, and the result is that this absolutely exact fidelity has restored a lucidity which was not wanting in Rabelais's time, but which had since been obscured. All who have come after Jannet have followed in his path, and there is no reason for straying from it.

FRANCIS RABELAIS.

To the Honoured, Noble Translator of Rabelais.

Rabelais, whose wit prodigiously was made,

All men, professions, actions to invade,

With so much furious vigour, as if it

Had lived o'er each of them, and each had quit,

Yet with such happy sleight and careless skill,

As, like the serpent, doth with laughter kill,

So that although his noble leaves appear

Antic and Gottish, and dull souls forbear

To turn them o'er, lest they should only find

Nothing but savage monsters of a mind,—

No shapen beauteous thoughts; yet when the wise

Seriously strip him of his wild disguise,

Melt down his dross, refine his massy ore,

And polish that which seem'd rough-cast before,

Search his deep sense, unveil his hidden mirth,

And make that fiery which before seem'd earth

(Conquering those things of highest consequence,

What's difficult of language or of sense),

He will appear some noble table writ

In the old Egyptian hieroglyphic wit;

Where, though you monsters and grotescoes see,

You meet all mysteries of philosophy.

For he was wise and sovereignly bred

To know what mankind is, how 't may be led:

He stoop'd unto them, like that wise man, who

Rid on a stick, when 's children would do so.

For we are easy sullen things, and must

Be laugh'd aright, and cheated into trust;

Whilst a black piece of phlegm, that lays about

Dull menaces, and terrifies the rout,

And cajoles it, with all its peevish strength

Piteously stretch'd and botch'd up into length,

Whilst the tired rabble sleepily obey

Such opiate talk, and snore away the day,

By all his noise as much their minds relieves,

As caterwauling of wild cats frights thieves.

But Rabelais was another thing, a man

Made up of all that art and nature can

Form from a fiery genius,—he was one

Whose soul so universally was thrown

Through all the arts of life, who understood

Each stratagem by which we stray from good;

So that he best might solid virtue teach,

As some 'gainst sins of their own bosoms preach:

He from wise choice did the true means prefer,

In the fool's coat acting th' philosopher.

Thus hoary Aesop's beasts did mildly tame

Fierce man, and moralize him into shame;

Thus brave romances, while they seem to lay

Great trains of lust, platonic love display;

Thus would old Sparta, if a seldom chance

Show'd a drunk slave, teach children temperance;

Thus did the later poets nobly bring

The scene to height, making the fool the king.

And, noble sir, you vigorously have trod

In this hard path, unknown, un-understood

By its own countrymen, 'tis you appear

Our full enjoyment which was our despair,

Scattering his mists, cheering his cynic frowns

(For radiant brightness now dark Rabelais crowns),

Leaving your brave heroic cares, which must

Make better mankind and embalm your dust,

So undeceiving us, that now we see

All wit in Gascon and in Cromarty,

Besides that Rabelais is convey'd to us,

And that our Scotland is not barbarous.

J. De la Salle.

Rablophila.

The First Decade.

The Commendation.

Musa! canas nostrorum in testimonium Amorum, Et Gargantueas perpetuato faces, Utque homini tali resultet nobilis Eccho: Quicquid Fama canit, Pantagruelis erit.

The Argument.

Here I intend mysteriously to sing

With a pen pluck'd from Fame's own wing,

Of Gargantua that learn'd breech-wiping king.

Decade the First.

I.

Help me, propitious stars; a mighty blaze

Benumbs me! I must sound the praise

Of him hath turn'd this crabbed work in such heroic phrase.

II.

What wit would not court martyrdom to hold

Upon his head a laurel of gold,

Where for each rich conceit a Pumpion-pearl is told:

III.

And such a one is this, art's masterpiece,

A thing ne'er equall'd by old Greece:

A thing ne'er match'd as yet, a real Golden Fleece.

IV.

Vice is a soldier fights against mankind;

Which you may look but never find:

For 'tis an envious thing, with cunning interlined.

V.

And thus he rails at drinking all before 'em,

And for lewd women does be-whore 'em,

And brings their painted faces and black patches to th' quorum.

VI.

To drink he was a furious enemy

Contented with a six-penny—

(with diamond hatband, silver spurs, six horses.) pie—

VII.

And for tobacco's pate-rotunding smoke,

Much had he said, and much more spoke,

But 'twas not then found out, so the design was broke.

VIII.

Muse! Fancy! Faith! come now arise aloud,

Assembled in a blue-vein'd cloud,

And this tall infant in angelic arms now shroud.

IX.

To praise it further I would now begin

Were 't now a thoroughfare and inn,

It harbours vice, though 't be to catch it in a gin.

X.

Therefore, my Muse, draw up thy flowing sail,

And acclamate a gentle hail

With all thy art and metaphors, which must prevail.

Jam prima Oceani pars est praeterita nostri.

Imparibus restat danda secunda modis.

Quam si praestiterit mentem Daemon malus addam,

Cum sapiens totus prodierit Rabelais.

Malevolus.

(Reader, the Errata, which in this book are not a few, are casually lost; and therefore the Translator, not having leisure to collect them again, craves thy pardon for such as thou may'st meet with.)

The Author's Prologue to the First Book.

Most noble and illustrious drinkers, and you thrice precious pockified blades (for to you, and none else, do I dedicate my writings), Alcibiades, in that dialogue of Plato's, which is entitled The Banquet, whilst he was setting forth the praises of his schoolmaster Socrates (without all question the prince of philosophers), amongst other discourses to that purpose, said that he resembled the Silenes. Silenes of old were little boxes, like those we now may see in the shops of apothecaries, painted on the outside with wanton toyish figures, as harpies, satyrs, bridled geese, horned hares, saddled ducks, flying goats, thiller harts, and other such-like counterfeited pictures at discretion, to excite people unto laughter, as Silenus himself, who was the foster-father of good Bacchus, was wont to do; but within those capricious caskets were carefully preserved and kept many rich jewels and fine drugs, such as balm, ambergris, amomon, musk, civet, with several kinds of precious stones, and other things of great price. Just such another thing was Socrates. For to have eyed his outside, and esteemed of him by his exterior appearance, you would not have given the peel of an onion for him, so deformed he was in body, and ridiculous in his gesture. He had a sharp pointed nose, with the look of a bull, and countenance of a fool: he was in his carriage simple, boorish in his apparel, in fortune poor, unhappy in his wives, unfit for all offices in the commonwealth, always laughing, tippling, and merrily carousing to everyone, with continual gibes and jeers, the better by those means to conceal his divine knowledge. Now, opening this box you would have found within it a heavenly and inestimable drug, a more than human understanding, an admirable virtue, matchless learning, invincible courage, unimitable sobriety, certain contentment of mind, perfect assurance, and an incredible misregard of all that for which men commonly do so much watch, run, sail, fight, travel, toil and turmoil themselves.