MASTER FRANCIS RABELAIS

FIVE BOOKS OF THE LIVES,

HEROIC DEEDS AND SAYINGS OF

GARGANTUA AND HIS SON PANTAGRUEL

Book IV.

More: Book I,Book II,Book III,Book IV,Book V

Translated into English by

Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty

and

Peter Antony Motteux

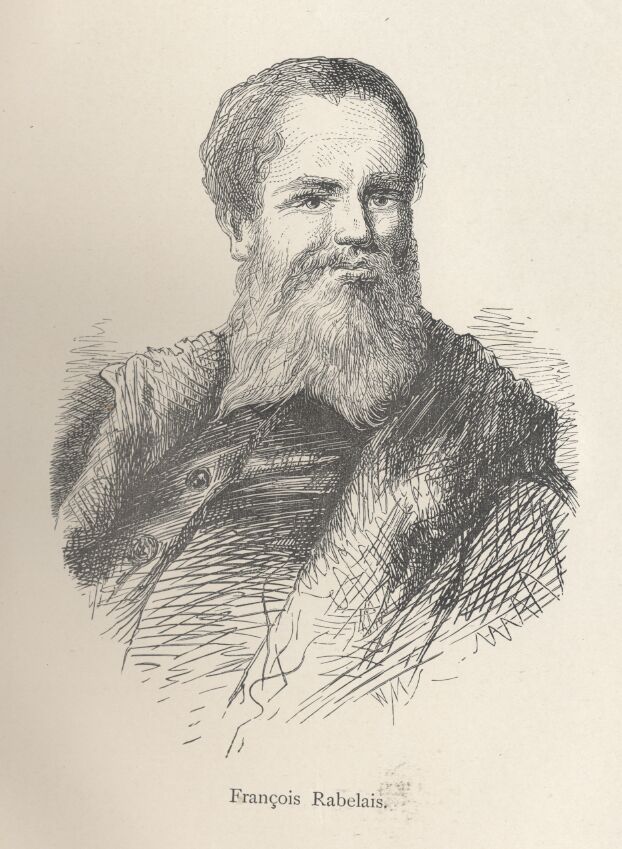

The text of the first Two Books of Rabelais has been reprinted from the first edition (1653) of Urquhart's translation. Footnotes initialled 'M.' are drawn from the Maitland Club edition (1838); other footnotes are by the translator. Urquhart's translation of Book III. appeared posthumously in 1693, with a new edition of Books I. and II., under Motteux's editorship. Motteux's rendering of Books IV. and V. followed in 1708. Occasionally (as the footnotes indicate) passages omitted by Motteux have been restored from the 1738 copy edited by Ozell.

CONTENTS

Chapter 4.I.—How Pantagruel went to sea to visit the oracle of Bacbuc, alias the Holy Bottle.

Chapter 4.II.—How Pantagruel bought many rarities in the island of Medamothy.

Chapter 4.IV.—How Pantagruel writ to his father Gargantua, and sent him several curiosities.

Chapter 4.V.—How Pantagruel met a ship with passengers returning from Lanternland.

Chapter 4.VI.—How, the fray being over, Panurge cheapened one of Dingdong's sheep.

Chapter 4.VII.—Which if you read you'll find how Panurge bargained with Dingdong.

Chapter 4.VIII.—How Panurge caused Dingdong and his sheep to be drowned in the sea.

Chapter 4.X.—How Pantagruel went ashore at the island of Chely, where he saw King St. Panigon.

Chapter 4.XI.—Why monks love to be in kitchens.

Chapter 4.XIII.—How, like Master Francis Villon, the Lord of Basche commended his servants.

Chapter 4.XIV.—A further account of catchpoles who were drubbed at Basche's house.

Chapter 4.XV.—How the ancient custom at nuptials is renewed by the catchpole.

Chapter 4.XVI.—How Friar John made trial of the nature of the catchpoles.

Chapter 4.XVIII.—How Pantagruel met with a great storm at sea.

Chapter 4.XIX.—What countenances Panurge and Friar John kept during the storm.

Chapter 4.XX.—How the pilots were forsaking their ships in the greatest stress of weather.

Chapter 4.XXII.—An end of the storm.

Chapter 4.XXIII.—How Panurge played the good fellow when the storm was over.

Chapter 4.XXIV.—How Panurge was said to have been afraid without reason during the storm.

Chapter 4.XXV.—How, after the storm, Pantagruel went on shore in the islands of the Macreons.

Chapter 4.XXVI.—How the good Macrobius gave us an account of the mansion and decease of the heroes.

Chapter 4.XXVIII.—How Pantagruel related a very sad story of the death of the heroes.

Chapter 4.XXIX.—How Pantagruel sailed by the Sneaking Island, where Shrovetide reigned.

Chapter 4.XXX.—How Shrovetide is anatomized and described by Xenomanes.

Chapter 4.XXXI.—Shrovetide's outward parts anatomized.

Chapter 4.XXXII.—A continuation of Shrovetide's countenance.

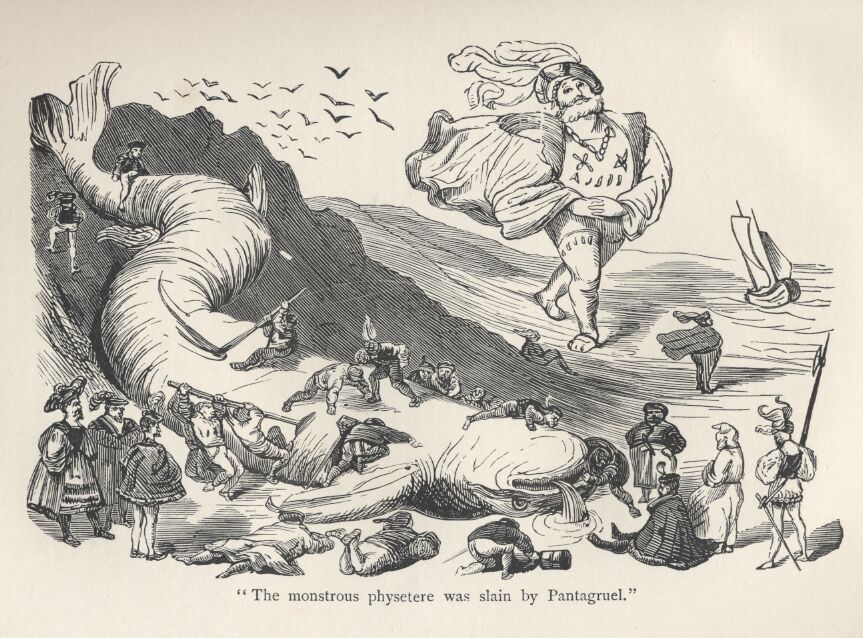

Chapter 4.XXXIV.—How the monstrous physeter was slain by Pantagruel.

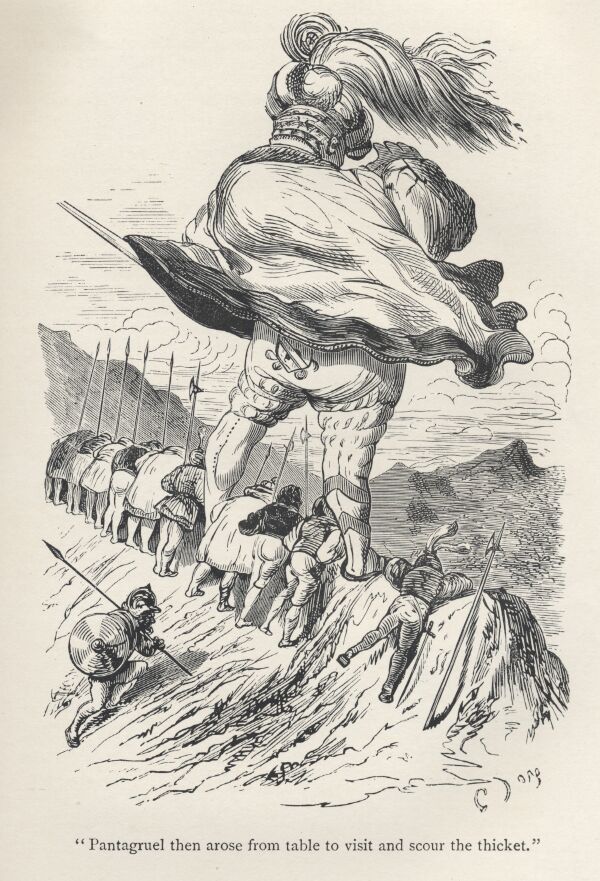

Chapter 4.XXXVI.—How the wild Chitterlings laid an ambuscado for Pantagruel.

Chapter 4.XXXVIII.—How Chitterlings are not to be slighted by men.

Chapter 4.XXXIX.—How Friar John joined with the cooks to fight the Chitterlings.

Chapter 4.XL.—How Friar John fitted up the sow; and of the valiant cooks that went into it.

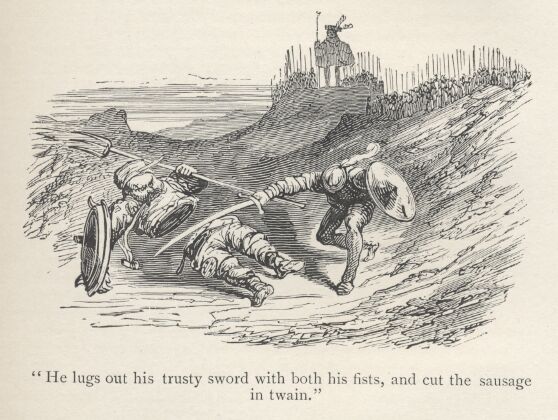

Chapter 4.XLI.—How Pantagruel broke the Chitterlings at the knees.

Chapter 4.XLII.—How Pantagruel held a treaty with Niphleseth, Queen of the Chitterlings.

Chapter 4.XLIII.—How Pantagruel went into the island of Ruach.

Chapter 4.XLIV.—How small rain lays a high wind.

Chapter 4.XLV.—How Pantagruel went ashore in the island of Pope-Figland.

Chapter 4.XLVI.—How a junior devil was fooled by a husbandman of Pope-Figland.

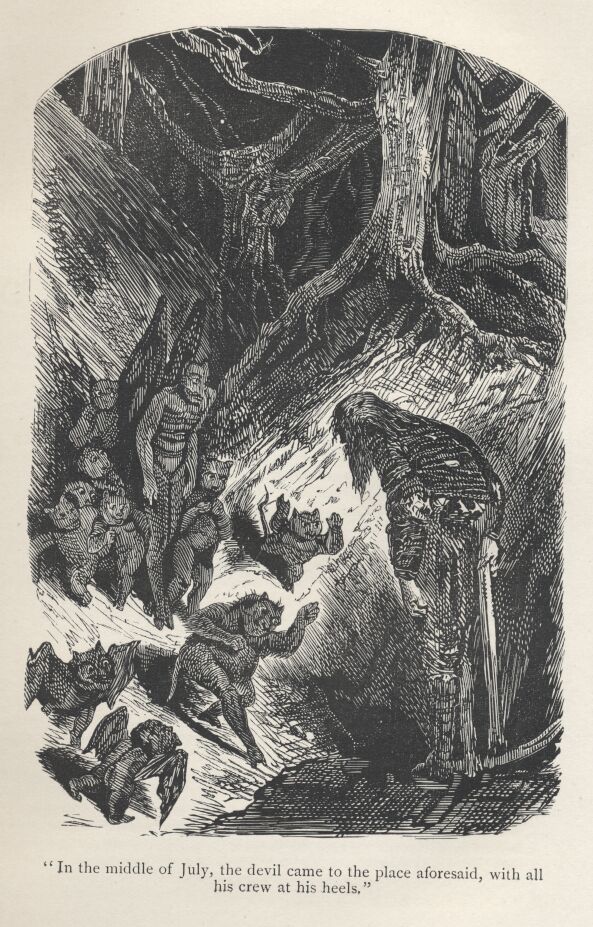

Chapter 4.XLVII.—How the devil was deceived by an old woman of Pope-Figland.

Chapter 4.XLVIII.—How Pantagruel went ashore at the island of Papimany.

Chapter 4.XLIX.—How Homenas, Bishop of Papimany, showed us the Uranopet decretals.

Chapter 4.L.—How Homenas showed us the archetype, or representation of a pope.

Chapter 4.LI.—Table-talk in praise of the decretals.

Chapter 4.LII.—A continuation of the miracles caused by the decretals.

Chapter 4.LIII.—How by the virtue of the decretals, gold is subtilely drawn out of France to Rome.

Chapter 4.LIV.—How Homenas gave Pantagruel some bon-Christian pears.

Chapter 4.LV.—How Pantagruel, being at sea, heard various unfrozen words.

Chapter 4.LVI.—How among the frozen words Pantagruel found some odd ones.

Chapter 4.LX.—What the Gastrolaters sacrificed to their god on interlarded fish-days.

Chapter 4.LXI.—How Gaster invented means to get and preserve corn.

Chapter 4.LXII.—How Gaster invented an art to avoid being hurt or touched by cannon-balls.

Chapter 4.LXIV.—How Pantagruel gave no answer to the problems.

Chapter 4.LXV.—How Pantagruel passed the time with his servants.

Chapter 4.LXVI.—How, by Pantagruel's order, the Muses were saluted near the isle of Ganabim.

List of Illustrations

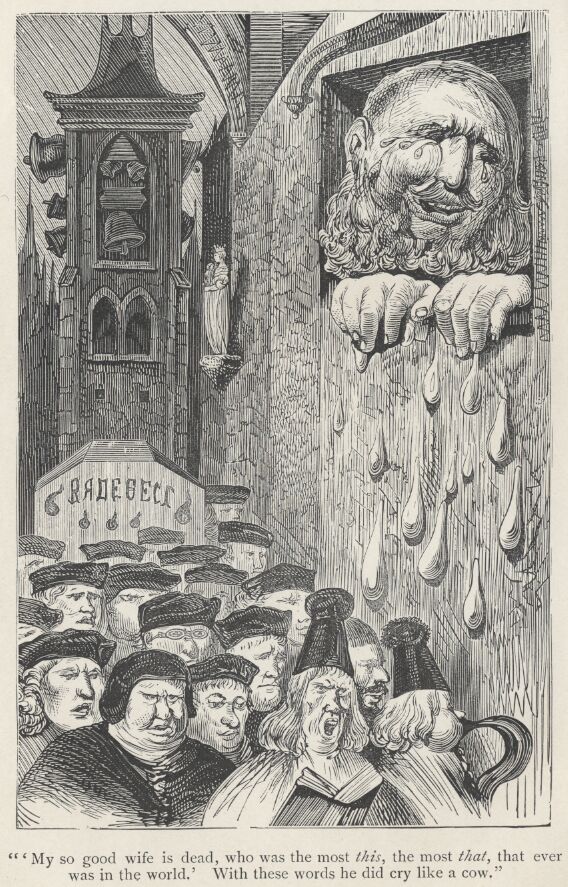

He Did Cry Like a Cow—frontispiece

Rabelais Dissecting Society—portrait2

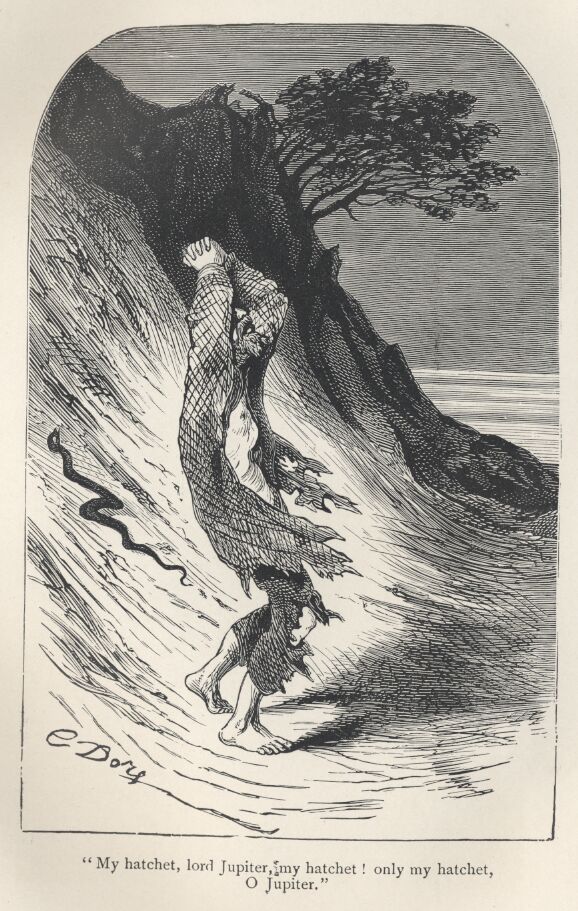

My Hatchet, Lord Jupeter—4-00-400

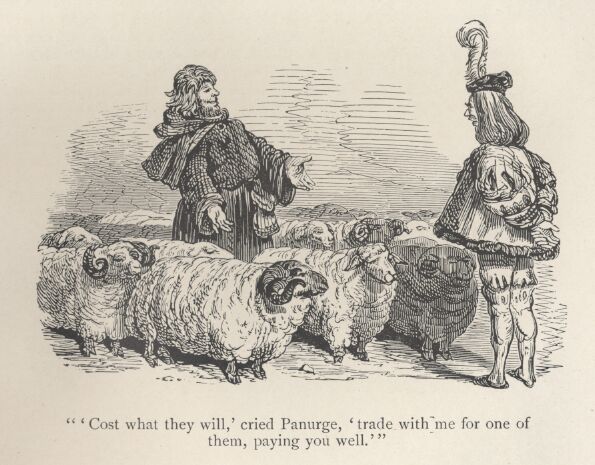

Cost What They Will, Trade With Me—4-07-420

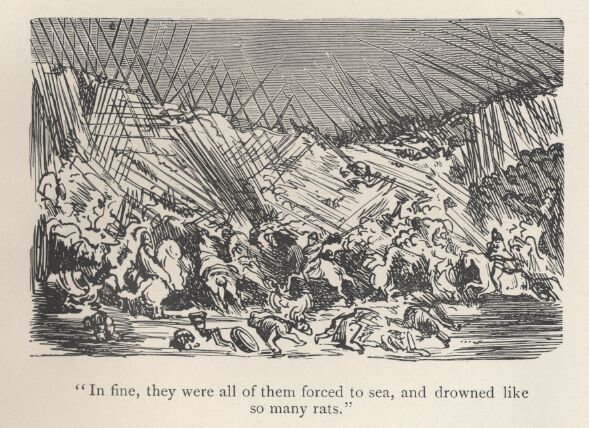

All of Them Forced to Sea and Drowned—4-08-422

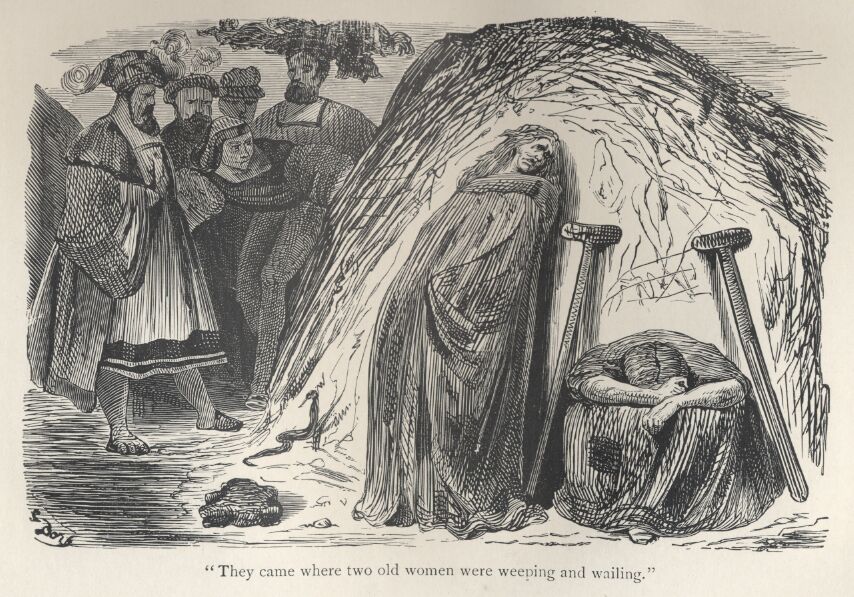

Two Old Women Were Weeping and Wailing—4-19-446

Physetere Was Slain by Pantagruel—4-35-472

Pantagruel Arose to Scour the Thicket—4-36-474

Cut the Sausage in Twain—4-41-482

The Devil Came to the Place—4-48-496

Appointed Cows to Furnish Milk—4-51-500

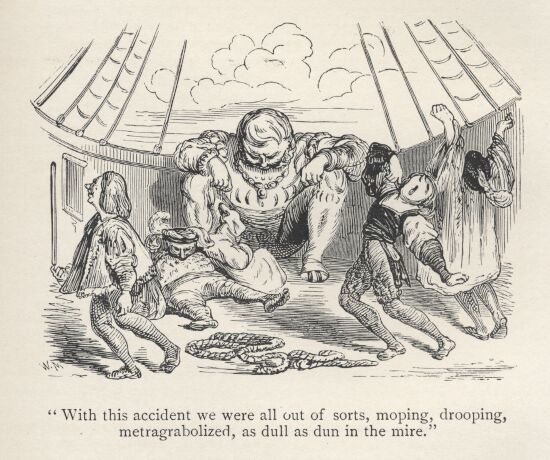

We Were All out of Sorts—4-63-524

THE FOURTH BOOK

The Translator's Preface.

Reader,—I don't know what kind of a preface I must write to find thee courteous, an epithet too often bestowed without a cause. The author of this work has been as sparing of what we call good nature, as most readers are nowadays. So I am afraid his translator and commentator is not to expect much more than has been showed them. What's worse, there are but two sorts of taking prefaces, as there are but two kinds of prologues to plays; for Mr. Bays was doubtless in the right when he said that if thunder and lightning could not fright an audience into complaisance, the sight of the poet with a rope about his neck might work them into pity. Some, indeed, have bullied many of you into applause, and railed at your faults that you might think them without any; and others, more safely, have spoken kindly of you, that you might think, or at least speak, as favourably of them, and be flattered into patience. Now, I fancy, there's nothing less difficult to attempt than the first method; for, in this blessed age, 'tis as easy to find a bully without courage, as a whore without beauty, or a writer without wit; though those qualifications are so necessary in their respective professions. The mischief is, that you seldom allow any to rail besides yourselves, and cannot bear a pride which shocks your own. As for wheedling you into a liking of a work, I must confess it seems the safest way; but though flattery pleases you well when it is particular, you hate it, as little concerning you, when it is general. Then we knights of the quill are a stiff-necked generation, who as seldom care to seem to doubt the worth of our writings, and their being liked, as we love to flatter more than one at a time; and had rather draw our pens, and stand up for the beauty of our works (as some arrant fools use to do for that of their mistresses) to the last drop of our ink. And truly this submission, which sometimes wheedles you into pity, as seldom decoys you into love, as the awkward cringing of an antiquated fop, as moneyless as he is ugly, affects an experienced fair one. Now we as little value your pity as a lover his mistress's, well satisfied that it is only a less uncivil way of dismissing us. But what if neither of these two ways will work upon you, of which doleful truth some of our playwrights stand so many living monuments? Why, then, truly I think on no other way at present but blending the two into one; and, from this marriage of huffing and cringing, there will result a new kind of careless medley, which, perhaps, will work upon both sorts of readers, those who are to be hectored, and those whom we must creep to. At least, it is like to please by its novelty; and it will not be the first monster that has pleased you when regular nature could not do it.

If uncommon worth, lively wit, and deep learning, wove into wholesome satire, a bold, good, and vast design admirably pursued, truth set out in its true light, and a method how to arrive to its oracle, can recommend a work, I am sure this has enough to please any reasonable man. The three books published some time since, which are in a manner an entire work, were kindly received; yet, in the French, they come far short of these two, which are also entire pieces; for the satire is all general here, much more obvious, and consequently more entertaining. Even my long explanatory preface was not thought improper. Though I was so far from being allowed time to make it methodical, that at first only a few pages were intended; yet as fast as they were printed I wrote on, till it proved at last like one of those towns built little at first, then enlarged, where you see promiscuously an odd variety of all sorts of irregular buildings. I hope the remarks I give now will not please less; for, as I have translated the work which they explain, I had more time to make them, though as little to write them. It would be needless to give here a large account of my performance; for, after all, you readers care no more for this or that apology, or pretence of Mr. Translator, if the version does not please you, than we do for a blundering cook's excuse after he has spoiled a good dish in the dressing. Nor can the first pretend to much praise, besides that of giving his author's sense in its full extent, and copying his style, if it is to be copied; since he has no share in the invention or disposition of what he translates. Yet there was no small difficulty in doing Rabelais justice in that double respect; the obsolete words and turns of phrase, and dark subjects, often as darkly treated, make the sense hard to be understood even by a Frenchman, and it cannot be easy to give it the free easy air of an original; for even what seems most common talk in one language, is what is often the most difficult to be made so in another; and Horace's thoughts of comedy may be well applied to this:

Creditur, ex medio quia res arcessit, habere Sudoris minimum; sed habet commoedia tantum Plus oneris, quanto veniae minus.

Far be it from me, for all this, to value myself upon hitting the words of cant in which my drolling author is so luxuriant; for though such words have stood me in good stead, I scarce can forbear thinking myself unhappy in having insensibly hoarded up so much gibberish and Billingsgate trash in my memory; nor could I forbear asking of myself, as an Italian cardinal said on another account, D'onde hai tu pigliato tante coglionerie? Where the devil didst thou rake up all these fripperies?

It was not less difficult to come up to the author's sublime expressions. Nor would I have attempted such a task, but that I was ambitious of giving a view of the most valuable work of the greatest genius of his age, to the Mecaenas and best genius of this. For I am not overfond of so ungrateful a task as translating, and would rejoice to see less versions and more originals; so the latter were not as bad as many of the first are, through want of encouragement. Some indeed have deservedly gained esteem by translating; yet not many condescend to translate, but such as cannot invent; though to do the first well requires often as much genius as to do the latter.

I wish, reader, thou mayest be as willing to do my author justice, as I have strove to do him right. Yet, if thou art a brother of the quill, it is ten to one thou art too much in love with thy own dear productions to admire those of one of thy trade. However, I know three or four who have not such a mighty opinion of themselves; but I'll not name them, lest I should be obliged to place myself among them. If thou art one of those who, though they never write, criticise everyone that does; avaunt!—Thou art a professed enemy of mankind and of thyself, who wilt never be pleased nor let anybody be so, and knowest no better way to fame than by striving to lessen that of others; though wouldst thou write thou mightst be soon known, even by the butterwomen, and fly through the world in bandboxes. If thou art of the dissembling tribe, it is thy office to rail at those books which thou huggest in a corner. If thou art one of those eavesdroppers, who would have their moroseness be counted gravity, thou wilt condemn a mirth which thou art past relishing; and I know no other way to quit the score than by writing (as like enough I may) something as dull, or duller than thyself, if possible. If thou art one of those critics in dressing, those extempores of fortune, who, having lost a relation and got an estate, in an instant set up for wit and every extravagance, thou'lt either praise or discommend this book, according to the dictates of some less foolish than thyself, perhaps of one of those who, being lodged at the sign of the box and dice, will know better things than to recommend to thee a work which bids thee beware of his tricks. This book might teach thee to leave thy follies; but some will say it does not signify much to some fools whether they are so or not; for when was there a fool that thought himself one? If thou art one of those who would put themselves upon us for learned men in Greek and Hebrew, yet are mere blockheads in English, and patch together old pieces of the ancients to get themselves clothes out of them, thou art too severely mauled in this work to like it. Who then will? some will cry. Nay, besides these, many societies that make a great figure in the world are reflected on in this book; which caused Rabelais to study to be dark, and even bedaub it with many loose expressions, that he might not be thought to have any other design than to droll; in a manner bewraying his book that his enemies might not bite it. Truly, though now the riddle is expounded, I would advise those who read it not to reflect on the author, lest he be thought to have been beforehand with them, and they be ranked among those who have nothing to show for their honesty but their money, nothing for their religion but their dissembling, or a fat benefice, nothing for their wit but their dressing, for their nobility but their title, for their gentility but their sword, for their courage but their huffing, for their preferment but their assurance, for their learning but their degrees, or for their gravity but their wrinkles or dulness. They had better laugh at one another here, as it is the custom of the world. Laughing is of all professions; the miser may hoard, the spendthrift squander, the politician plot, the lawyer wrangle, and the gamester cheat; still their main design is to be able to laugh at one another; and here they may do it at a cheap and easy rate. After all, should this work fail to please the greater number of readers, I am sure it cannot miss being liked by those who are for witty mirth and a chirping bottle; though not by those solid sots who seem to have drudged all their youth long only that they might enjoy the sweet blessing of getting drunk every night in their old age. But those men of sense and honour who love truth and the good of mankind in general above all other things will undoubtedly countenance this work. I will not gravely insist upon its usefulness, having said enough of it in the preface (Motteux' Preface to vol. I of Rabelais, ed. 1694.) to the first part. I will only add, that as Homer in his Odyssey makes his hero wander ten years through most parts of the then known world, so Rabelais, in a three months' voyage, makes Pantagruel take a view of almost all sorts of people and professions; with this difference, however, between the ancient mythologist and the modern, that while the Odyssey has been compared to a setting sun in respect to the Iliads, Rabelais' last work, which is this Voyage to the Oracle of the Bottle (by which he means truth) is justly thought his masterpiece, being wrote with more spirit, salt, and flame, than the first part of his works. At near seventy years of age, his genius, far from being drained, seemed to have acquired fresh vigour and new graces the more it exerted itself; like those rivers which grow more deep, large, majestic, and useful by their course. Those who accuse the French of being as sparing of their wit as lavish of their words will find an Englishman in our author. I must confess indeed that my countrymen and other southern nations temper the one with the other in a manner as they do their wine with water, often just dashing the latter with a little of the first. Now here men love to drink their wine pure; nay, sometimes it will not satisfy unless in its very quintessence, as in brandies; though an excess of this betrays want of sobriety, as much as an excess of wit betrays a want of judgment. But I must conclude, lest I be justly taxed with wanting both. I will only add, that as every language has its peculiar graces, seldom or never to be acquired by a foreigner, I cannot think I have given my author those of the English in every place; but as none compelled me to write, I fear to ask a pardon which yet the generous temper of this nation makes me hope to obtain. Albinus, a Roman, who had written in Greek, desired in his preface to be forgiven his faults of language; but Cato asked him in derision whether any had forced him to write in a tongue of which he was not an absolute master. Lucullus wrote a history in the same tongue, and said he had scattered some false Greek in it to let the world know it was the work of a Roman. I will not say as much of my writings, in which I study to be as little incorrect as the hurry of business and shortness of time will permit; but I may better say, as Tully did of the history of his consulship, which he also had written in Greek, that what errors may be found in the diction are crept in against my intent. Indeed, Livius Andronicus and Terence, the one a Greek, the other a Carthaginian, wrote successfully in Latin, and the latter is perhaps the most perfect model of the purity and urbanity of that tongue; but I ought not to hope for the success of those great men. Yet am I ambitious of being as subservient to the useful diversion of the ingenious of this nation as I can, which I have endeavoured in this work, with hopes to attempt some greater tasks if ever I am happy enough to have more leisure. In the meantime it will not displease me, if it is known that this is given by one who, though born and educated in France, has the love and veneration of a loyal subject for this nation, one who, by a fatality, which with many more made him say,

Nos patriam fugimus et dulcia linquimus arva,

is obliged to make the language of these happy regions as natural to him as he can, and thankfully say with the rest, under this Protestant government,

Deus nobis haec otia fecit.

The Author's Epistle Dedicatory.

To the most Illustrious Prince and most Reverend Lord Odet, Cardinal de Chastillon.

You know, most illustrious prince, how often I have been, and am daily pressed and required by great numbers of eminent persons, to proceed in the Pantagruelian fables; they tell me that many languishing, sick, and disconsolate persons, perusing them, have deceived their grief, passed their time merrily, and been inspired with new joy and comfort. I commonly answer that I aimed not at glory and applause when I diverted myself with writing, but only designed to give by my pen, to the absent who labour under affliction, that little help which at all times I willingly strive to give to the present that stand in need of my art and service. Sometimes I at large relate to them how Hippocrates in several places, and particularly in lib. 6. Epidem., describing the institution of the physician his disciple, and also Soranus of Ephesus, Oribasius, Galen, Hali Abbas, and other authors, have descended to particulars, in the prescription of his motions, deportment, looks, countenance, gracefulness, civility, cleanliness of face, clothes, beard, hair, hands, mouth, even his very nails; as if he were to play the part of a lover in some comedy, or enter the lists to fight some enemy. And indeed the practice of physic is properly enough compared by Hippocrates to a fight, and also to a farce acted between three persons, the patient, the physician, and the disease. Which passage has sometimes put me in mind of Julia's saying to Augustus her father. One day she came before him in a very gorgeous, loose, lascivious dress, which very much displeased him, though he did not much discover his discontent. The next day she put on another, and in a modest garb, such as the chaste Roman ladies wore, came into his presence. The kind father could not then forbear expressing the pleasure which he took to see her so much altered, and said to her: Oh! how much more this garb becomes and is commendable in the daughter of Augustus. But she, having her excuse ready, answered: This day, sir, I dressed myself to please my father's eye; yesterday, to gratify that of my husband. Thus disguised in looks and garb, nay even, as formerly was the fashion, with a rich and pleasant gown with four sleeves, which was called philonium according to Petrus Alexandrinus in 6. Epidem., a physician might answer to such as might find the metamorphosis indecent: Thus have I accoutred myself, not that I am proud of appearing in such a dress, but for the sake of my patient, whom alone I wholly design to please, and no wise offend or dissatisfy. There is also a passage in our father Hippocrates, in the book I have named, which causes some to sweat, dispute, and labour; not indeed to know whether the physician's frowning, discontented, and morose Catonian look render the patient sad, and his joyful, serene, and pleasing countenance rejoice him; for experience teaches us that this is most certain; but whether such sensations of grief or pleasure are produced by the apprehension of the patient observing his motions and qualities in his physician, and drawing from thence conjectures of the end and catastrophe of his disease; as, by his pleasing look, joyful and desirable events, and by his sorrowful and unpleasing air, sad and dismal consequences; or whether those sensations be produced by a transfusion of the serene or gloomy, aerial or terrestrial, joyful or melancholic spirits of the physician into the person of the patient, as is the opinion of Plato, Averroes, and others.

Above all things, the forecited authors have given particular directions to physicians about the words, discourse, and converse which they ought to have with their patients; everyone aiming at one point, that is, to rejoice them without offending God, and in no wise whatsoever to vex or displease them. Which causes Herophilus much to blame the physician Callianax, who, being asked by a patient of his, Shall I die? impudently made him this answer:

Patroclus died, whom all allow By much a better man than you.

Another, who had a mind to know the state of his distemper, asking him, after our merry Patelin's way: Well, doctor, does not my water tell you I shall die? He foolishly answered, No; if Latona, the mother of those lovely twins, Phoebus and Diana, begot thee. Galen, lib. 4, Comment. 6. Epidem., blames much also Quintus his tutor, who, a certain nobleman of Rome, his patient, saying to him, You have been at breakfast, my master, your breath smells of wine; answered arrogantly, Yours smells of fever; which is the better smell of the two, wine or a putrid fever? But the calumny of certain cannibals, misanthropes, perpetual eavesdroppers, has been so foul and excessive against me, that it had conquered my patience, and I had resolved not to write one jot more. For the least of their detractions were that my books are all stuffed with various heresies, of which, nevertheless, they could not show one single instance; much, indeed, of comical and facetious fooleries, neither offending God nor the king (and truly I own they are the only subject and only theme of these books), but of heresy not a word, unless they interpreted wrong, and against all use of reason and common language, what I had rather suffer a thousand deaths, if it were possible, than have thought; as who should make bread to be stone, a fish to be a serpent, and an egg to be a scorpion. This, my lord, emboldened me once to tell you, as I was complaining of it in your presence, that if I did not esteem myself a better Christian than they show themselves towards me, and if my life, writings, words, nay thoughts, betrayed to me one single spark of heresy, or I should in a detestable manner fall into the snares of the spirit of detraction, Diabolos, who, by their means, raises such crimes against me; I would then, like the phoenix, gather dry wood, kindle a fire, and burn myself in the midst of it. You were then pleased to say to me that King Francis, of eternal memory, had been made sensible of those false accusations; and that having caused my books (mine, I say, because several, false and infamous, have been wickedly laid to me) to be carefully and distinctly read to him by the most learned and faithful anagnost in this kingdom, he had not found any passage suspicious; and that he abhorred a certain envious, ignorant, hypocritical informer, who grounded a mortal heresy on an n put instead of an m by the carelessness of the printers.

As much was done by his son, our most gracious, virtuous, and blessed sovereign, Henry, whom Heaven long preserve! so that he granted you his royal privilege and particular protection for me against my slandering adversaries.

You kindly condescended since to confirm me these happy news at Paris; and also lately, when you visited my Lord Cardinal du Bellay, who, for the benefit of his health, after a lingering distemper, was retired to St. Maur, that place (or rather paradise) of salubrity, serenity, conveniency, and all desirable country pleasures.

Thus, my lord, under so glorious a patronage, I am emboldened once more to draw my pen, undaunted now and secure; with hopes that you will still prove to me, against the power of detraction, a second Gallic Hercules in learning, prudence, and eloquence; an Alexicacos in virtue, power, and authority; you, of whom I may truly say what the wise monarch Solomon saith of Moses, that great prophet and captain of Israel, Ecclesiast. 45: A man fearing and loving God, who found favour in the sight of all flesh, well-beloved both of God and man; whose memorial is blessed. God made him like to the glorious saints, and magnified him so, that his enemies stood in fear of him; and for him made wonders; made him glorious in the sight of kings, gave him a commandment for his people, and by him showed his light; he sanctified him in his faithfulness and meekness, and chose him out of all men. By him he made us to hear his voice, and caused by him the law of life and knowledge to be given.

Accordingly, if I shall be so happy as to hear anyone commend those merry composures, they shall be adjured by me to be obliged and pay their thanks to you alone, as also to offer their prayers to Heaven for the continuance and increase of your greatness; and to attribute no more to me than my humble and ready obedience to your commands; for by your most honourable encouragement you at once have inspired me with spirit and with invention; and without you my heart had failed me, and the fountain-head of my animal spirits had been dry. May the Lord keep you in his blessed mercy!

My Lord,

Your most humble, and most devoted Servant,

Francis Rabelais, Physician.

Paris, this 28th of January, MDLII.

The Author's Prologue.

Good people, God save and keep you! Where are you? I can't see you: stay—I'll saddle my nose with spectacles—oh, oh! 'twill be fair anon: I see you. Well, you have had a good vintage, they say: this is no bad news to Frank, you may swear. You have got an infallible cure against thirst: rarely performed of you, my friends! You, your wives, children, friends, and families are in as good case as hearts can wish; it is well, it is as I would have it: God be praised for it, and if such be his will, may you long be so. For my part, I am thereabouts, thanks to his blessed goodness; and by the means of a little Pantagruelism (which you know is a certain jollity of mind, pickled in the scorn of fortune), you see me now hale and cheery, as sound as a bell, and ready to drink, if you will. Would you know why I'm thus, good people? I will even give you a positive answer —Such is the Lord's will, which I obey and revere; it being said in his word, in great derision to the physician neglectful of his own health, Physician, heal thyself.

Galen had some knowledge of the Bible, and had conversed with the Christians of his time, as appears lib. 11. De Usu Partium; lib. 2. De Differentiis Pulsuum, cap. 3, and ibid. lib. 3. cap. 2. and lib. De Rerum Affectibus (if it be Galen's). Yet 'twas not for any such veneration of holy writ that he took care of his own health. No, it was for fear of being twitted with the saying so well known among physicians:

Iatros allon autos elkesi bruon. He boasts of healing poor and rich, Yet is himself all over itch.

This made him boldly say, that he did not desire to be esteemed a physician, if from his twenty-eighth year to his old age he had not lived in perfect health, except some ephemerous fevers, of which he soon rid himself; yet he was not naturally of the soundest temper, his stomach being evidently bad. Indeed, as he saith, lib. 5, De Sanitate tuenda, that physician will hardly be thought very careful of the health of others who neglects his own. Asclepiades boasted yet more than this; for he said that he had articled with fortune not to be reputed a physician if he could be said to have been sick since he began to practise physic to his latter age, which he reached, lusty in all his members and victorious over fortune; till at last the old gentleman unluckily tumbled down from the top of a certain ill-propped and rotten staircase, and so there was an end of him.

If by some disaster health is fled from your worships to the right or to the left, above or below, before or behind, within or without, far or near, on this side or the other side, wheresoever it be, may you presently, with the help of the Lord, meet with it. Having found it, may you immediately claim it, seize it, and secure it. The law allows it; the king would have it so; nay, you have my advice for it. Neither more nor less than the law-makers of old did fully empower a master to claim and seize his runaway servant wherever he might be found. Odds-bodikins, is it not written and warranted by the ancient customs of this noble, so rich, so flourishing realm of France, that the dead seizes the quick? See what has been declared very lately in that point by that learned, wise, courteous, humane and just civilian, Andrew Tiraqueau, one of the judges in the most honourable court of Parliament at Paris. Health is our life, as Ariphron the Sicyonian wisely has it; without health life is not life, it is not living life: abios bios, bios abiotos. Without health life is only a languishment and an image of death. Therefore, you that want your health, that is to say, that are dead, seize the quick; secure life to yourselves, that is to say, health.

I have this hope in the Lord, that he will hear our supplications, considering with what faith and zeal we pray, and that he will grant this our wish because it is moderate and mean. Mediocrity was held by the ancient sages to be golden, that is to say, precious, praised by all men, and pleasing in all places. Read the sacred Bible, you will find the prayers of those who asked moderately were never unanswered. For example, little dapper Zaccheus, whose body and relics the monks of St. Garlick, near Orleans, boast of having, and nickname him St. Sylvanus; he only wished to see our blessed Saviour near Jerusalem. It was but a small request, and no more than anybody then might pretend to. But alas! he was but low-built; and one of so diminutive a size, among the crowd, could not so much as get a glimpse of him. Well then he struts, stands on tiptoes, bustles, and bestirs his stumps, shoves and makes way, and with much ado clambers up a sycamore. Upon this, the Lord, who knew his sincere affection, presented himself to his sight, and was not only seen by him, but heard also; nay, what is more, he came to his house and blessed his family.

One of the sons of the prophets in Israel felling would near the river Jordan, his hatchet forsook the helve and fell to the bottom of the river; so he prayed to have it again ('twas but a small request, mark ye me), and having a strong faith, he did not throw the hatchet after the helve, as some spirits of contradiction say by way of scandalous blunder, but the helve after the hatchet, as you all properly have it. Presently two great miracles were seen: up springs the hatchet from the bottom of the water, and fixes itself to its old acquaintance the helve. Now had he wished to coach it to heaven in a fiery chariot like Elias, to multiply in seed like Abraham, be as rich as Job, strong as Samson, and beautiful as Absalom, would he have obtained it, d'ye think? I' troth, my friends, I question it very much.

Now I talk of moderate wishes in point of hatchet (but harkee me, be sure you don't forget when we ought to drink), I will tell you what is written among the apologues of wise Aesop the Frenchman. I mean the Phrygian and Trojan, as Max. Planudes makes him; from which people, according to the most faithful chroniclers, the noble French are descended. Aelian writes that he was of Thrace and Agathias, after Herodotus, that he was of Samos; 'tis all one to Frank.

In his time lived a poor honest country fellow of Gravot, Tom Wellhung by name, a wood-cleaver by trade, who in that low drudgery made shift so to pick up a sorry livelihood. It happened that he lost his hatchet. Now tell me who ever had more cause to be vexed than poor Tom? Alas, his whole estate and life depended on his hatchet; by his hatchet he earned many a fair penny of the best woodmongers or log-merchants among whom he went a-jobbing; for want of his hatchet he was like to starve; and had death but met with him six days after without a hatchet, the grim fiend would have mowed him down in the twinkling of a bedstaff. In this sad case he began to be in a heavy taking, and called upon Jupiter with the most eloquent prayers—for you know necessity was the mother of eloquence. With the whites of his eyes turned up towards heaven, down on his marrow-bones, his arms reared high, his fingers stretched wide, and his head bare, the poor wretch without ceasing was roaring out, by way of litany, at every repetition of his supplications, My hatchet, Lord Jupiter, my hatchet! my hatchet! only my hatchet, O Jupiter, or money to buy another, and nothing else! alas, my poor hatchet!

Jupiter happened then to be holding a grand council about certain urgent affairs, and old gammer Cybele was just giving her opinion, or, if you would rather have it so, it was young Phoebus the beau; but, in short, Tom's outcries and lamentations were so loud that they were heard with no small amazement at the council-board, by the whole consistory of the gods. What a devil have we below, quoth Jupiter, that howls so horridly? By the mud of Styx, have not we had all along, and have not we here still enough to do, to set to rights a world of damned puzzling businesses of consequence? We made an end of the fray between Presthan, King of Persia, and Soliman the Turkish emperor, we have stopped up the passages between the Tartars and the Muscovites; answered the Xeriff's petition; done the same to that of Golgots Rays; the state of Parma's despatched; so is that of Maidenburg, that of Mirandola, and that of Africa, that town on the Mediterranean which we call Aphrodisium; Tripoli by carelessness has got a new master; her hour was come.

Here are the Gascons cursing and damning, demanding the restitution of their bells.

In yonder corner are the Saxons, Easterlings, Ostrogoths, and Germans, nations formerly invincible, but now aberkeids, bridled, curbed, and brought under a paltry diminutive crippled fellow; they ask us revenge, relief, restitution of their former good sense and ancient liberty.

But what shall we do with this same Ramus and this Galland, with a pox to them, who, surrounded with a swarm of their scullions, blackguard ragamuffins, sizars, vouchers, and stipulators, set together by the ears the whole university of Paris? I am in a sad quandary about it, and for the heart's blood of me cannot tell yet with whom of the two to side.

Both seem to me notable fellows, and as true cods as ever pissed. The one has rose-nobles, I say fine and weighty ones; the other would gladly have some too. The one knows something; the other's no dunce. The one loves the better sort of men; the other's beloved by 'em. The one is an old cunning fox; the other with tongue and pen, tooth and nail, falls foul on the ancient orators and philosophers, and barks at them like a cur.

What thinkest thou of it, say, thou bawdy Priapus? I have found thy counsel just before now, et habet tua mentula mentem.

King Jupiter, answered Priapus, standing up and taking off his cowl, his snout uncased and reared up, fiery and stiffly propped, since you compare the one to a yelping snarling cur and the other to sly Reynard the fox, my advice is, with submission, that without fretting or puzzling your brains any further about 'em, without any more ado, even serve 'em both as, in the days of yore, you did the dog and the fox. How? asked Jupiter; when? who were they? where was it? You have a rare memory, for aught I see! returned Priapus. This right worshipful father Bacchus, whom we have here nodding with his crimson phiz, to be revenged on the Thebans had got a fairy fox, who, whatever mischief he did, was never to be caught or wronged by any beast that wore a head.

The noble Vulcan here present had framed a dog of Monesian brass, and with long puffing and blowing put the spirit of life into him; he gave it to you, you gave it your Miss Europa, Miss Europa gave it Minos, Minos gave it Procris, Procris gave it Cephalus. He was also of the fairy kind; so that, like the lawyers of our age, he was too hard for all other sorts of creatures; nothing could scape the dog. Now who should happen to meet but these two? What do you think they did? Dog by his destiny was to take fox, and fox by his fate was not to be taken.

The case was brought before your council: you protested that you would not act against the fates; and the fates were contradictory. In short, the end and result of the matter was, that to reconcile two contradictions was an impossibility in nature. The very pang put you into a sweat; some drops of which happening to light on the earth, produced what the mortals call cauliflowers. All our noble consistory, for want of a categorical resolution, were seized with such a horrid thirst, that above seventy-eight hogsheads of nectar were swilled down at that sitting. At last you took my advice, and transmogrified them into stones; and immediately got rid of your perplexity, and a truce with thirst was proclaimed through this vast Olympus. This was the year of flabby cods, near Teumessus, between Thebes and Chalcis.

After this manner, it is my opinion that you should petrify this dog and this fox. The metamorphosis will not be incongruous; for they both bear the name of Peter. And because, according to the Limosin proverb, to make an oven's mouth there must be three stones, you may associate them with Master Peter du Coignet, whom you formerly petrified for the same cause. Then those three dead pieces shall be put in an equilateral trigone somewhere in the great temple at Paris—in the middle of the porch, if you will—there to perform the office of extinguishers, and with their noses put out the lighted candles, torches, tapers, and flambeaux; since, while they lived, they still lighted, ballock-like, the fire of faction, division, ballock sects, and wrangling among those idle bearded boys, the students. And this will be an everlasting monument to show that those puny self-conceited pedants, ballock-framers, were rather contemned than condemned by you. Dixi, I have said my say.

You deal too kindly by them, said Jupiter, for aught I see, Monsieur Priapus. You do not use to be so kind to everybody, let me tell you; for as they seek to eternize their names, it would be much better for them to be thus changed into hard stones than to return to earth and putrefaction. But now to other matters. Yonder behind us, towards the Tuscan sea and the neighbourhood of Mount Apennine, do you see what tragedies are stirred up by certain topping ecclesiastical bullies? This hot fit will last its time, like the Limosins' ovens, and then will be cooled, but not so fast.

We shall have sport enough with it; but I foresee one inconveniency; for methinks we have but little store of thunder ammunition since the time that you, my fellow gods, for your pastime lavished them away to bombard new Antioch, by my particular permission; as since, after your example, the stout champions who had undertaken to hold the fortress of Dindenarois against all comers fairly wasted their powder with shooting at sparrows, and then, not having wherewith to defend themselves in time of need, valiantly surrendered to the enemy, who were already packing up their awls, full of madness and despair, and thought on nothing but a shameful retreat. Take care this be remedied, son Vulcan; rouse up your drowsy Cyclopes, Asteropes, Brontes, Arges, Polyphemus, Steropes, Pyracmon, and so forth, set them at work, and make them drink as they ought.

Never spare liquor to such as are at hot work. Now let us despatch this bawling fellow below. You, Mercury, go see who it is, and know what he wants. Mercury looked out at heaven's trapdoor, through which, as I am told, they hear what is said here below. By the way, one might well enough mistake it for the scuttle of a ship; though Icaromenippus said it was like the mouth of a well. The light-heeled deity saw that it was honest Tom, who asked for his lost hatchet; and accordingly he made his report to the synod. Marry, said Jupiter, we are finely helped up, as if we had now nothing else to do here but to restore lost hatchets. Well, he must have it then for all this, for so 'tis written in the Book of Fate (do you hear?), as well as if it was worth the whole duchy of Milan. The truth is, the fellow's hatchet is as much to him as a kingdom to a king. Come, come, let no more words be scattered about it; let him have his hatchet again.

Now, let us make an end of the difference betwixt the Levites and mole-catchers of Landerousse. Whereabouts were we? Priapus was standing in the chimney-corner, and having heard what Mercury had reported, said in a most courteous and jovial manner: King Jupiter, while by your order and particular favour I was garden-keeper-general on earth, I observed that this word hatchet is equivocal to many things; for it signifies a certain instrument by the means of which men fell and cleave timber. It also signifies (at least I am sure it did formerly) a female soundly and frequently thumpthumpriggletickletwiddletobyed. Thus I perceived that every cock of the game used to call his doxy his hatchet; for with that same tool (this he said lugging out and exhibiting his nine-inch knocker) they so strongly and resolutely shove and drive in their helves, that the females remain free from a fear epidemical amongst their sex, viz., that from the bottom of the male's belly the instrument should dangle at his heel for want of such feminine props. And I remember, for I have a member, and a memory too, ay, and a fine memory, large enough to fill a butter-firkin; I remember, I say, that one day of tubilustre (horn-fair) at the festivals of goodman Vulcan in May, I heard Josquin Des Prez, Olkegan, Hobrecht, Agricola, Brumel, Camelin, Vigoris, De la Fage, Bruyer, Prioris, Seguin, De la Rue, Midy, Moulu, Mouton, Gascogne, Loyset, Compere, Penet, Fevin, Rousee, Richard Fort, Rousseau, Consilion, Constantio Festi, Jacquet Bercan, melodiously singing the following catch on a pleasant green:

Long John to bed went to his bride, And laid a mallet by his side: What means this mallet, John? saith she. Why! 'tis to wedge thee home, quoth he. Alas! cried she, the man's a fool: What need you use a wooden tool? When lusty John does to me come, He never shoves but with his bum.

Nine Olympiads, and an intercalary year after (I have a rare member, I would say memory; but I often make blunders in the symbolization and colligance of those two words), I heard Adrian Villart, Gombert, Janequin, Arcadet, Claudin, Certon, Manchicourt, Auxerre, Villiers, Sandrin, Sohier, Hesdin, Morales, Passereau, Maille, Maillart, Jacotin, Heurteur, Verdelot, Carpentras, L'Heritier, Cadeac, Doublet, Vermont, Bouteiller, Lupi, Pagnier, Millet, Du Moulin, Alaire, Maraut, Morpain, Gendre, and other merry lovers of music, in a private garden, under some fine shady trees, round about a bulwark of flagons, gammons, pasties, with several coated quails, and laced mutton, waggishly singing:

Since tools without their hafts are useless lumber, And hatchets without helves are of that number; That one may go in t'other, and may match it, I'll be the helve, and thou shalt be the hatchet.

Now would I know what kind of hatchet this bawling Tom wants? This threw all the venerable gods and goddesses into a fit of laughter, like any microcosm of flies; and even set limping Vulcan a-hopping and jumping smoothly three or four times for the sake of his dear. Come, come, said Jupiter to Mercury, run down immediately, and cast at the poor fellow's feet three hatchets: his own, another of gold, and a third of massy silver, all of one size; then having left it to his will to take his choice, if he take his own, and be satisfied with it, give him the other two; if he take another, chop his head off with his own; and henceforth serve me all those losers of hatchets after that manner. Having said this, Jupiter, with an awkward turn of his head, like a jackanapes swallowing of pills, made so dreadful a phiz that all the vast Olympus quaked again. Heaven's foot messenger, thanks to his low-crowned narrow-brimmed hat, his plume of feathers, heel-pieces, and running stick with pigeon wings, flings himself out at heaven's wicket, through the idle deserts of the air, and in a trice nimbly alights upon the earth, and throws at friend Tom's feet the three hatchets, saying unto him: Thou hast bawled long enough to be a-dry; thy prayers and request are granted by Jupiter: see which of these three is thy hatchet, and take it away with thee. Wellhung lifts up the golden hatchet, peeps upon it, and finds it very heavy; then staring on Mercury, cries, Codszouks, this is none of mine; I won't ha't: the same he did with the silver one, and said, 'Tis not this neither, you may e'en take them again. At last he takes up his own hatchet, examines the end of the helve, and finds his mark there; then, ravished with joy, like a fox that meets some straggling poultry, and sneering from the tip of the nose, he cried, By the mass, this is my hatchet, master god; if you will leave it me, I will sacrifice to you a very good and huge pot of milk brimful, covered with fine strawberries, next ides of May.

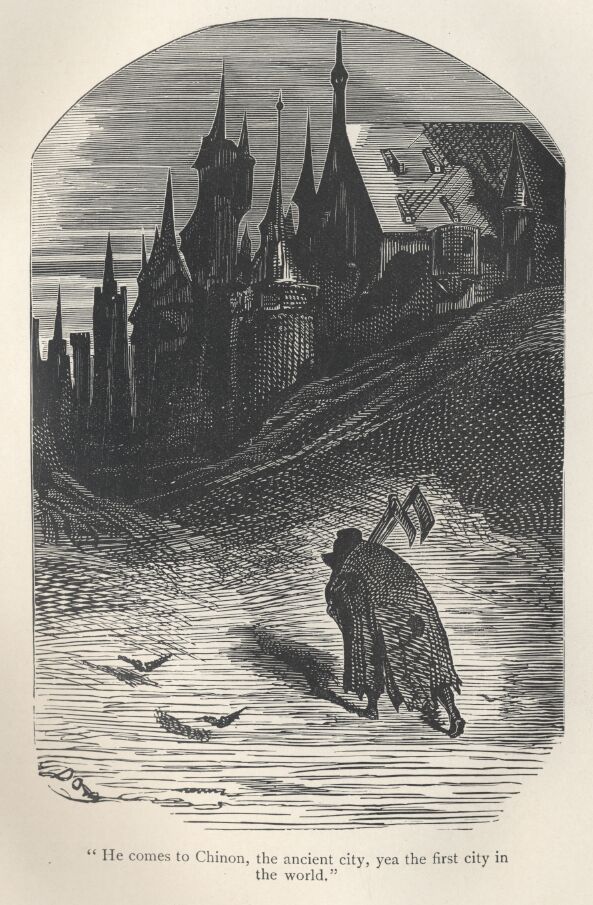

Honest fellow, said Mercury, I leave it thee; take it; and because thou hast wished and chosen moderately in point of hatchet, by Jupiter's command I give thee these two others; thou hast now wherewith to make thyself rich: be honest. Honest Tom gave Mercury a whole cartload of thanks, and revered the most great Jupiter. His old hatchet he fastens close to his leathern girdle, and girds it above his breech like Martin of Cambray; the two others, being more heavy, he lays on his shoulder. Thus he plods on, trudging over the fields, keeping a good countenance amongst his neighbours and fellow-parishioners, with one merry saying or other after Patelin's way. The next day, having put on a clean white jacket, he takes on his back the two precious hatchets and comes to Chinon, the famous city, noble city, ancient city, yea, the first city in the world, according to the judgment and assertion of the most learned Massorets. At Chinon he turned his silver hatchet into fine testons, crown-pieces, and other white cash; his golden hatchet into fine angels, curious ducats, substantial ridders, spankers, and rose-nobles; then with them purchases a good number of farms, barns, houses, out-houses, thatched houses, stables, meadows, orchards, fields, vineyards, woods, arable lands, pastures, ponds, mills, gardens, nurseries, oxen, cows, sheep, goats, swine, hogs, asses, horses, hens, cocks, capons, chickens, geese, ganders, ducks, drakes, and a world of all other necessaries, and in a short time became the richest man in the country, nay, even richer than that limping scrape-good Maulevrier. His brother bumpkins, and the other yeomen and country-puts thereabouts, perceiving his good fortune, were not a little amazed, insomuch that their former pity of poor Tom was soon changed into an envy of his so great and unexpected rise; and as they could not for their souls devise how this came about, they made it their business to pry up and down, and lay their heads together, to inquire, seek, and inform themselves by what means, in what place, on what day, what hour, how, why, and wherefore, he had come by this great treasure.

At last, hearing it was by losing his hatchet, Ha, ha! said they, was there no more to do but to lose a hatchet to make us rich? Mum for that; 'tis as easy as pissing a bed, and will cost but little. Are then at this time the revolutions of the heavens, the constellations of the firmament, and aspects of the planets such, that whosoever shall lose a hatchet shall immediately grow rich? Ha, ha, ha! by Jove, you shall e'en be lost, an't please you, my dear hatchet. With this they all fairly lost their hatchets out of hand. The devil of one that had a hatchet left; he was not his mother's son that did not lose his hatchet. No more was wood felled or cleaved in that country through want of hatchets. Nay, the Aesopian apologue even saith that certain petty country gents of the lower class, who had sold Wellhung their little mill and little field to have wherewithal to make a figure at the next muster, having been told that his treasure was come to him by that only means, sold the only badge of their gentility, their swords, to purchase hatchets to go lose them, as the silly clodpates did, in hopes to gain store of chink by that loss.

You would have truly sworn they had been a parcel of your petty spiritual usurers, Rome-bound, selling their all, and borrowing of others, to buy store of mandates, a pennyworth of a new-made pope.

Now they cried out and brayed, and prayed and bawled, and lamented, and invoked Jupiter: My hatchet! my hatchet! Jupiter, my hatchet! on this side, My hatchet! on that side, My hatchet! Ho, ho, ho, ho, Jupiter, my hatchet! The air round about rung again with the cries and howlings of these rascally losers of hatchets.

Mercury was nimble in bringing them hatchets; to each offering that which he had lost, as also another of gold, and a third of silver.

Every he still was for that of gold, giving thanks in abundance to the great giver, Jupiter; but in the very nick of time that they bowed and stooped to take it from the ground, whip, in a trice, Mercury lopped off their heads, as Jupiter had commanded; and of heads thus cut off the number was just equal to that of the lost hatchets.

You see how it is now; you see how it goes with those who in the simplicity of their hearts wish and desire with moderation. Take warning by this, all you greedy, fresh-water sharks, who scorn to wish for anything under ten thousand pounds; and do not for the future run on impudently, as I have sometimes heard you wishing, Would to God I had now one hundred seventy-eight millions of gold! Oh! how I should tickle it off. The deuce on you, what more might a king, an emperor, or a pope wish for? For that reason, indeed, you see that after you have made such hopeful wishes, all the good that comes to you of it is the itch or the scab, and not a cross in your breeches to scare the devil that tempts you to make these wishes: no more than those two mumpers, wishers after the custom of Paris; one of whom only wished to have in good old gold as much as hath been spent, bought, and sold in Paris, since its first foundations were laid, to this hour; all of it valued at the price, sale, and rate of the dearest year in all that space of time. Do you think the fellow was bashful? Had he eaten sour plums unpeeled? Were his teeth on edge, I pray you? The other wished Our Lady's Church brimful of steel needles, from the floor to the top of the roof, and to have as many ducats as might be crammed into as many bags as might be sewed with each and everyone of those needles, till they were all either broke at the point or eye. This is to wish with a vengeance! What think you of it? What did they get by't, in your opinion? Why at night both my gentlemen had kibed heels, a tetter in the chin, a churchyard cough in the lungs, a catarrh in the throat, a swingeing boil at the rump, and the devil of one musty crust of a brown george the poor dogs had to scour their grinders with. Wish therefore for mediocrity, and it shall be given unto you, and over and above yet; that is to say, provided you bestir yourself manfully, and do your best in the meantime.

Ay, but say you, God might as soon have given me seventy-eight thousand as the thirteenth part of one half; for he is omnipotent, and a million of gold is no more to him than one farthing. Oh, ho! pray tell me who taught you to talk at this rate of the power and predestination of God, poor silly people? Peace, tush, st, st, st! fall down before his sacred face and own the nothingness of your nothing.

Upon this, O ye that labour under the affliction of the gout, I ground my hopes; firmly believing, that if so it pleases the divine goodness, you shall obtain health; since you wish and ask for nothing else, at least for the present. Well, stay yet a little longer with half an ounce of patience.

The Genoese do not use, like you, to be satisfied with wishing health alone, when after they have all the livelong morning been in a brown study, talked, pondered, ruminated, and resolved in the counting-houses of whom and how they may squeeze the ready, and who by their craft must be hooked in, wheedled, bubbled, sharped, overreached, and choused; they go to the exchange, and greet one another with a Sanita e guadagno, Messer! health and gain to you, sir! Health alone will not go down with the greedy curmudgeons; they over and above must wish for gain, with a pox to 'em; ay, and for the fine crowns, or scudi di Guadaigne; whence, heaven be praised! it happens many a time that the silly wishers and woulders are baulked, and get neither.

Now, my lads, as you hope for good health, cough once aloud with lungs of leather; take me off three swingeing bumpers; prick up your ears; and you shall hear me tell wonders of the noble and good Pantagruel.

THE FOURTH BOOK.

Chapter 4.I.—How Pantagruel went to sea to visit the oracle of Bacbuc, alias the Holy Bottle.

In the month of June, on Vesta's holiday, the very numerical day on which Brutus, conquering Spain, taught its strutting dons to truckle under him, and that niggardly miser Crassus was routed and knocked on the head by the Parthians, Pantagruel took his leave of the good Gargantua, his royal father. The old gentleman, according to the laudable custom of the primitive Christians, devoutly prayed for the happy voyage of his son and his whole company, and then they took shipping at the port of Thalassa. Pantagruel had with him Panurge, Friar John des Entomeures, alias of the Funnels, Epistemon, Gymnast, Eusthenes, Rhizotome, Carpalin, cum multis aliis, his ancient servants and domestics; also Xenomanes, the great traveller, who had crossed so many dangerous roads, dikes, ponds, seas, and so forth, and was come some time before, having been sent for by Panurge.

For certain good causes and considerations him thereunto moving, he had left with Gargantua, and marked out, in his great and universal hydrographical chart, the course which they were to steer to visit the Oracle of the Holy Bottle Bacbuc. The number of ships were such as I described in the third book, convoyed by a like number of triremes, men of war, galleons, and feluccas, well-rigged, caulked, and stored with a good quantity of Pantagruelion.

All the officers, droggermen, pilots, captains, mates, boatswains, midshipmen, quartermasters, and sailors, met in the Thalamege, Pantagruel's principal flag-ship, which had in her stern for her ensign a huge large bottle, half silver well polished, the other half gold enamelled with carnation; whereby it was easy to guess that white and red were the colours of the noble travellers, and that they went for the word of the Bottle.

On the stern of the second was a lantern like those of the ancients, industriously made with diaphanous stone, implying that they were to pass by Lanternland. The third ship had for her device a fine deep china ewer. The fourth, a double-handed jar of gold, much like an ancient urn. The fifth, a famous can made of sperm of emerald. The sixth, a monk's mumping bottle made of the four metals together. The seventh, an ebony funnel, all embossed and wrought with gold after the Tauchic manner. The eighth, an ivy goblet, very precious, inlaid with gold. The ninth, a cup of fine Obriz gold. The tenth, a tumbler of aromatic agoloch (you call it lignum aloes) edged with Cyprian gold, after the Azemine make. The eleventh, a golden vine-tub of mosaic work. The twelfth, a runlet of unpolished gold, covered with a small vine of large Indian pearl of Topiarian work. Insomuch that there was not a man, however in the dumps, musty, sour-looked, or melancholic he were, not even excepting that blubbering whiner Heraclitus, had he been there, but seeing this noble convoy of ships and their devices, must have been seized with present gladness of heart, and, smiling at the conceit, have said that the travellers were all honest topers, true pitcher-men, and have judged by a most sure prognostication that their voyage, both outward and homeward-bound, would be performed in mirth and perfect health.

In the Thalamege, where was the general meeting, Pantagruel made a short but sweet exhortation, wholly backed with authorities from Scripture upon navigation; which being ended, with an audible voice prayers were said in the presence and hearing of all the burghers of Thalassa, who had flocked to the mole to see them take shipping. After the prayers was melodiously sung a psalm of the holy King David, which begins, When Israel went out of Egypt; and that being ended, tables were placed upon deck, and a feast speedily served up. The Thalassians, who had also borne a chorus in the psalm, caused store of belly-timber to be brought out of their houses. All drank to them; they drank to all; which was the cause that none of the whole company gave up what they had eaten, nor were sea-sick, with a pain at the head and stomach; which inconveniency they could not so easily have prevented by drinking, for some time before, salt water, either alone or mixed with wine; using quinces, citron peel, juice of pomegranates, sourish sweetmeats, fasting a long time, covering their stomachs with paper, or following such other idle remedies as foolish physicians prescribe to those that go to sea.

Having often renewed their tipplings, each mother's son retired on board his own ship, and set sail all so fast with a merry gale at south-east; to which point of the compass the chief pilot, James Brayer by name, had shaped his course, and fixed all things accordingly. For seeing that the Oracle of the Holy Bottle lay near Cathay, in the Upper India, his advice, and that of Xenomanes also, was not to steer the course which the Portuguese use, while sailing through the torrid zone, and Cape Bona Speranza, at the south point of Africa, beyond the equinoctial line, and losing sight of the northern pole, their guide, they make a prodigious long voyage; but rather to keep as near the parallel of the said India as possible, and to tack to the westward of the said pole, so that winding under the north, they might find themselves in the latitude of the port of Olone, without coming nearer it for fear of being shut up in the frozen sea; whereas, following this canonical turn, by the said parallel, they must have that on the right to the eastward, which at their departure was on their left.

This proved a much shorter cut; for without shipwreck, danger, or loss of men, with uninterrupted good weather, except one day near the island of the Macreons, they performed in less than four months the voyage of Upper India, which the Portuguese, with a thousand inconveniences and innumerable dangers, can hardly complete in three years. And it is my opinion, with submission to better judgments, that this course was perhaps steered by those Indians who sailed to Germany, and were honourably received by the King of the Swedes, while Quintus Metellus Celer was proconsul of the Gauls; as Cornelius Nepos, Pomponius Mela, and Pliny after them tell us.

Chapter 4.II.—How Pantagruel bought many rarities in the island of Medamothy.

That day and the two following they neither discovered land nor anything new; for they had formerly sailed that way: but on the fourth they made an island called Medamothy, of a fine and delightful prospect, by reason of the vast number of lighthouses and high marble towers in its circuit, which is not less than that of Canada (sic). Pantagruel, inquiring who governed there, heard that it was King Philophanes, absent at that time upon account of the marriage of his brother Philotheamon with the infanta of the kingdom of Engys.

Hearing this, he went ashore in the harbour, and while every ship's crew watered, passed his time in viewing divers pictures, pieces of tapestry, animals, fishes, birds, and other exotic and foreign merchandises, which were along the walks of the mole and in the markets of the port. For it was the third day of the great and famous fair of the place, to which the chief merchants of Africa and Asia resorted. Out of these Friar John bought him two rare pictures; in one of which the face of a man that brings in an appeal was drawn to the life; and in the other a servant that wants a master, with every needful particular, action, countenance, look, gait, feature, and deportment, being an original by Master Charles Charmois, principal painter to King Megistus; and he paid for them in the court fashion, with conge and grimace. Panurge bought a large picture, copied and done from the needle-work formerly wrought by Philomela, showing to her sister Progne how her brother-in-law Tereus had by force handselled her copyhold, and then cut out her tongue that she might not (as women will) tell tales. I vow and swear by the handle of my paper lantern that it was a gallant, a mirific, nay, a most admirable piece. Nor do you think, I pray you, that in it was the picture of a man playing the beast with two backs with a female; this had been too silly and gross: no, no; it was another-guise thing, and much plainer. You may, if you please, see it at Theleme, on the left hand as you go into the high gallery. Epistemon bought another, wherein were painted to the life the ideas of Plato and the atoms of Epicurus. Rhizotome purchased another, wherein Echo was drawn to the life. Pantagruel caused to be bought, by Gymnast, the life and deeds of Achilles, in seventy-eight pieces of tapestry, four fathom long, and three fathom broad, all of Phrygian silk, embossed with gold and silver; the work beginning at the nuptials of Peleus and Thetis, continuing to the birth of Achilles; his youth, described by Statius Papinius; his warlike achievements, celebrated by Homer; his death and obsequies, written by Ovid and Quintus Calaber; and ending at the appearance of his ghost, and Polyxena's sacrifice, rehearsed by Euripides.

He also caused to be bought three fine young unicorns; one of them a male of a chestnut colour, and two grey dappled females; also a tarand, whom he bought of a Scythian of the Gelones' country.

A tarand is an animal as big as a bullock, having a head like a stag, or a little bigger, two stately horns with large branches, cloven feet, hair long like that of a furred Muscovite, I mean a bear, and a skin almost as hard as steel armour. The Scythian said that there are but few tarands to be found in Scythia, because it varieth its colour according to the diversity of the places where it grazes and abides, and represents the colour of the grass, plants, trees, shrubs, flowers, meadows, rocks, and generally of all things near which it comes. It hath this common with the sea-pulp, or polypus, with the thoes, with the wolves of India, and with the chameleon, which is a kind of a lizard so wonderful that Democritus hath written a whole book of its figure and anatomy, as also of its virtue and propriety in magic. This I can affirm, that I have seen it change its colour, not only at the approach of things that have a colour, but by its own voluntary impulse, according to its fear or other affections; as, for example, upon a green carpet I have certainly seen it become green; but having remained there some time, it turned yellow, blue, tanned, and purple in course, in the same manner as you see a turkey-cock's comb change colour according to its passions. But what we find most surprising in this tarand is, that not only its face and skin, but also its hair could take whatever colour was about it. Near Panurge, with his kersey coat, its hair used to turn grey; near Pantagruel, with his scarlet mantle, its hair and skin grew red; near the pilot, dressed after the fashion of the Isiacs of Anubis in Egypt, its hair seemed all white, which two last colours the chameleons cannot borrow.

When the creature was free from any fear or affection, the colour of its hair was just such as you see that of the asses of Meung.

Chapter 4.III.—How Pantagruel received a letter from his father Gargantua, and of the strange way to have speedy news from far distant places.

While Pantagruel was taken up with the purchase of those foreign animals, the noise of ten guns and culverins, together with a loud and joyful cheer of all the fleet, was heard from the mole. Pantagruel looked towards the haven, and perceived that this was occasioned by the arrival of one of his father Gargantua's celoces, or advice-boats, named the Chelidonia; because on the stern of it was carved in Corinthian brass a sea-swallow, which is a fish as large as a dare-fish of Loire, all flesh, without scale, with cartilaginous wings (like a bat's) very long and broad, by the means of which I have seen them fly about three fathom above water, about a bow-shot. At Marseilles 'tis called lendole. And indeed that ship was as light as a swallow, so that it rather seemed to fly on the sea than to sail. Malicorne, Gargantua's esquire carver, was come in her, being sent expressly by his master to have an account of his son's health and circumstances, and to bring him credentials. When Malicorne had saluted Pantagruel, before the prince opened the letters, the first thing he said to him was, Have you here the Gozal, the heavenly messenger? Yes, sir, said he; here it is swaddled up in this basket. It was a grey pigeon, taken out of Gargantua's dove-house, whose young ones were just hatched when the advice-boat was going off.

If any ill fortune had befallen Pantagruel, he would have fastened some black ribbon to his feet; but because all things had succeeded happily hitherto, having caused it to be undressed, he tied to its feet a white ribbon, and without any further delay let it loose. The pigeon presently flew away, cutting the air with an incredible speed, as you know that there is no flight like a pigeon's, especially when it hath eggs or young ones, through the extreme care which nature hath fixed in it to relieve and be with its young; insomuch that in less than two hours it compassed in the air the long tract which the advice-boat, with all her diligence, with oars and sails, and a fair wind, could not go through in less than three days and three nights; and was seen as it went into the dove-house in its nest. Whereupon Gargantua, hearing that it had the white ribbon on, was joyful and secure of his son's welfare. This was the custom of the noble Gargantua and Pantagruel when they would have speedy news of something of great concern; as the event of some battle, either by sea or land; the surrendering or holding out of some strong place; the determination of some difference of moment; the safe or unhappy delivery of some queen or great lady; the death or recovery of their sick friends or allies, and so forth. They used to take the gozal, and had it carried from one to another by the post, to the places whence they desired to have news. The gozal, bearing either a black or white ribbon, according to the occurrences and accidents, used to remove their doubts at its return, making in the space of one hour more way through the air than thirty postboys could have done in one natural day. May not this be said to redeem and gain time with a vengeance, think you? For the like service, therefore, you may believe as a most true thing that in the dove-houses of their farms there were to be found all the year long store of pigeons hatching eggs or rearing their young. Which may be easily done in aviaries and voleries by the help of saltpetre and the sacred herb vervain.

The gozal being let fly, Pantagruel perused his father Gargantua's letter, the contents of which were as followeth:

My dearest Son,—The affection that naturally a father bears a beloved son is so much increased in me by reflecting on the particular gifts which by the divine goodness have been heaped on thee, that since thy departure it hath often banished all other thoughts out of my mind, leaving my heart wholly possessed with fear lest some misfortune has attended thy voyage; for thou knowest that fear was ever the attendant of true and sincere love. Now because, as Hesiod saith, A good beginning of anything is the half of it; or, Well begun's half done, according to the old saying; to free my mind from this anxiety I have expressly despatched Malicorne, that he may give me a true account of thy health at the beginning of thy voyage. For if it be good, and such as I wish it, I shall easily foresee the rest.

I have met with some diverting books, which the bearer will deliver thee; thou mayest read them when thou wantest to unbend and ease thy mind from thy better studies. He will also give thee at large the news at court. The peace of the Lord be with thee. Remember me to Panurge, Friar John, Epistemon, Xenomanes, Gymnast, and thy other principal domestics. Dated at our paternal seat, this 13th day of June.

Thy father and friend, Gargantua.

Chapter 4.IV.—How Pantagruel writ to his father Gargantua, and sent him several curiosities.

Pantagruel, having perused the letter, had a long conference with the esquire Malicorne; insomuch that Panurge, at last interrupting them, asked him, Pray, sir, when do you design to drink? When shall we drink? When shall the worshipful esquire drink? What a devil! have you not talked long enough to drink? It is a good motion, answered Pantagruel: go, get us something ready at the next inn; I think 'tis the Centaur. In the meantime he writ to Gargantua as followeth, to be sent by the aforesaid esquire:

Most gracious Father,—As our senses and animal faculties are more discomposed at the news of events unexpected, though desired (even to an immediate dissolution of the soul from the body), than if those accidents had been foreseen, so the coming of Malicorne hath much surprised and disordered me. For I had no hopes to see any of your servants, or to hear from you, before I had finished our voyage; and contented myself with the dear remembrance of your august majesty, deeply impressed in the hindmost ventricle of my brain, often representing you to my mind.

But since you have made me happy beyond expectation by the perusal of your gracious letter, and the faith I have in your esquire hath revived my spirits by the news of your welfare, I am as it were compelled to do what formerly I did freely, that is, first to praise the blessed Redeemer, who by his divine goodness preserves you in this long enjoyment of perfect health; then to return you eternal thanks for the fervent affection which you have for me your most humble son and unprofitable servant.

Formerly a Roman, named Furnius, said to Augustus, who had received his father into favour, and pardoned him after he had sided with Antony, that by that action the emperor had reduced him to this extremity, that for want of power to be grateful, both while he lived and after it, he should be obliged to be taxed with ingratitude. So I may say, that the excess of your fatherly affection drives me into such a strait, that I shall be forced to live and die ungrateful; unless that crime be redressed by the sentence of the Stoics, who say that there are three parts in a benefit, the one of the giver, the other of the receiver, the third of the remunerator; and that the receiver rewards the giver when he freely receives the benefit and always remembers it; as, on the contrary, that man is most ungrateful who despises and forgets a benefit. Therefore, being overwhelmed with infinite favours, all proceeding from your extreme goodness, and on the other side wholly incapable of making the smallest return, I hope at least to free myself from the imputation of ingratitude, since they can never be blotted out of my mind; and my tongue shall never cease to own that to thank you as I ought transcends my capacity.

As for us, I have this assurance in the Lord's mercy and help, that the end of our voyage will be answerable to its beginning, and so it will be entirely performed in health and mirth. I will not fail to set down in a journal a full account of our navigation, that at our return you may have an exact relation of the whole.

I have found here a Scythian tarand, an animal strange and wonderful for the variations of colour on its skin and hair, according to the distinction of neighbouring things; it is as tractable and easily kept as a lamb. Be pleased to accept of it.

I also send you three young unicorns, which are the tamest of creatures.

I have conferred with the esquire, and taught him how they must be fed. These cannot graze on the ground by reason of the long horn on their forehead, but are forced to browse on fruit trees, or on proper racks, or to be fed by hand, with herbs, sheaves, apples, pears, barley, rye, and other fruits and roots, being placed before them.

I am amazed that ancient writers should report them to be so wild, furious, and dangerous, and never seen alive; far from it, you will find that they are the mildest things in the world, provided they are not maliciously offended. Likewise I send you the life and deeds of Achilles in curious tapestry; assuring you whatever rarities of animals, plants, birds, or precious stones, and others, I shall be able to find and purchase in our travels, shall be brought to you, God willing, whom I beseech, by his blessed grace, to preserve you.

From Medamothy, this 15th of June. Panurge, Friar John, Epistemon, Zenomanes, Gymnast, Eusthenes, Rhizotome, and Carpalin, having most humbly kissed your hand, return your salute a thousand times.

Your most dutiful son and servant, Pantagruel.

While Pantagruel was writing this letter, Malicorne was made welcome by all with a thousand goodly good-morrows and how-d'ye's; they clung about him so that I cannot tell you how much they made of him, how many humble services, how many from my love and to my love were sent with him. Pantagruel, having writ his letters, sat down at table with him, and afterwards presented him with a large chain of gold, weighing eight hundred crowns, between whose septenary links some large diamonds, rubies, emeralds, turquoise stones, and unions were alternately set in. To each of his bark's crew he ordered to be given five hundred crowns. To Gargantua, his father, he sent the tarand covered with a cloth of satin, brocaded with gold, and the tapestry containing the life and deeds of Achilles, with the three unicorns in friezed cloth of gold trappings; and so they left Medamothy—Malicorne to return to Gargantua, Pantagruel to proceed in his voyage, during which Epistemon read to him the books which the esquire had brought, and because he found them jovial and pleasant, I shall give you an account of them, if you earnestly desire it.

Chapter 4.V.—How Pantagruel met a ship with passengers returning from Lanternland.

On the fifth day we began already to wind by little and little about the pole; going still farther from the equinoctial line, we discovered a merchant-man to the windward of us. The joy for this was not small on both sides; we in hopes to hear news from sea, and those in the merchant-man from land. So we bore upon 'em, and coming up with them we hailed them; and finding them to be Frenchmen of Xaintonge, backed our sails and lay by to talk to them. Pantagruel heard that they came from Lanternland; which added to his joy, and that of the whole fleet. We inquired about the state of that country, and the way of living of the Lanterns; and were told that about the latter end of the following July was the time prefixed for the meeting of the general chapter of the Lanterns; and that if we arrived there at that time, as we might easily, we should see a handsome, honourable, and jolly company of Lanterns; and that great preparations were making, as if they intended to lanternize there to the purpose. We were told also that if we touched at the great kingdom of Gebarim, we should be honourably received and treated by the sovereign of that country, King Ohabe, who, as well as all his subjects, speaks Touraine French.

While we were listening to these news, Panurge fell out with one Dingdong, a drover or sheep-merchant of Taillebourg. The occasion of the fray was thus: